Labor Market and Social Security: Who bears the burden of the economic downturn?

Uladzimir Valetka

Summary

In 2015, the natural population decline was further reduced in Belarus, and net migration gain further increased; however, those two trends were not enough to stop the reduction of the workforce and the decrease in employment. Structural problems in the labor market still remain unresolved and will continue limiting the increase in the contribution of human capital to economic growth. Wages went down for the first time ever; however, employers’ unit labor costs decrease slower than labor productivity.

Social aid was intensified amid the recession; however, the welfare system is not designed to work in conditions of economic contraction, and the coverage and targeting accuracy of social programs in the least well-off quantile dropped, while poverty in rural areas was reported to have increased.

Trends:

- Reduction in the workforce and ageing of the employed population;

- Slower creation of new jobs;

- High labor turnover and ‘brain drain’;

- Slower reduction in labor costs compared with labor productivity, which may affect competitiveness;

- Increase in the pension age due to the deficit of the Social Security Fund;

- Failure of social programs to meet the new requirements of the economy in a recession.

Population

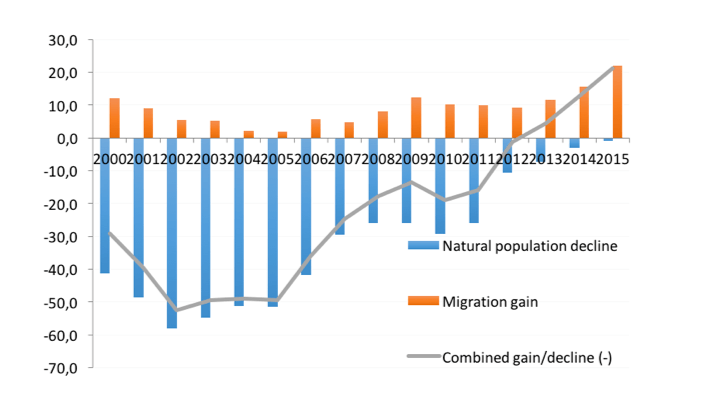

In 2015, the natural population decline was estimated at 621 people (Figure 1), which compares with 2,387 people in 2014.

In 2015, 119,509 babies were born in Belarus, and 120,230 people died. Belarus’s population reached 9,498,400 people at the end of 2015, up from 9,480,900 at the start of the year (an increase by 18,500 people).1 Rural population decreased by 27,600 people, to 2,128,300 people from 2,155,900 people. As in 2014, population decreased in all regions, except for the city of Minsk (up by 20,000 people) and the Minsk Region (up by 10,000 people).

Net migration gain amounted to 18,500 people in 2015 — it made up for the natural population loss, and ensured an increase in Belarus’s population by 18,000 people.

Belarus’s workforce kept decreasing, though: by more than 60,000 people in 2015. The decline is due to demographic factors that were analyzed in the previous issues of Belarusian Yearbook.2

The country’s demography policy still focuses on families with children: an additional 172,000 families received childcare allowances for children aged from 3 to 18, provided they have a child or children younger than 3 years of age. The family capital program was launched, envisaging the crediting of USD 10,000 to a deposit account of a family, where a third and subsequent child is born.3 In the first three quarters of 2015, USD 68 million was credited to parents’ accounts.

Labor market

In 2015, Belarus’s workforce averaged 4,482,600 people, down by 1.5% from 2014. According to Belstat, the country’s workforce decreased by 61,200 people in 2015, to 4,470,000 people in December 2015.4 Official unemployment remains low, at 1% of the economically active population (up from 0.5% in 2014). In late 2015, there were 46,000 officially unemployed people in the country. Last year, BYR 40 billion was spent on unemployment benefits, or 0.005% of GDP, some 80 times less than the average for transition economies.

The systemic ‘bottlenecks’ of the labor market observed in 2015 include.

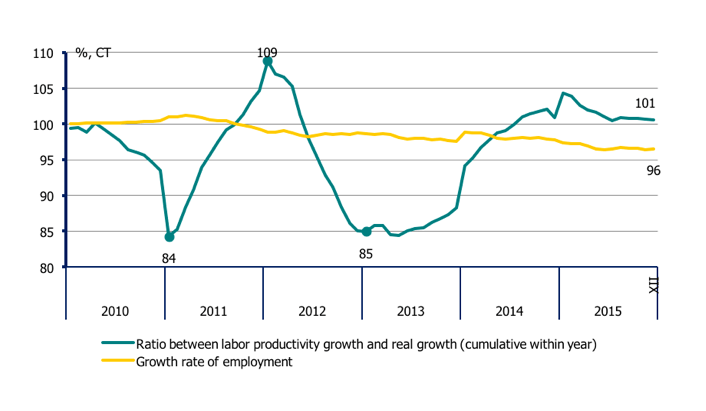

1. Passive redundancy policy and excessive employment. Starting from mid-2015, some 80,000–120,000 workers were on forced leaves or worked shorter weeks due to the drop in demand in the Russian market. Many state enterprises are supported as last resort employers. This strategy alleviates the short-term negative consequences of the growth of unemployment; however, the policy of supporting jobs, not workers, disrupts the logic of the dependence of demand for labor on demand for products and undermines the foundation for anticipated productivity gain. Productivity shrank faster in 2015 than labor costs fell (see Figure 2).

The burden of hidden unemployment was passed on from job centers to employers (unlike unemployment benefits, severance pays were relatively high, compared with elsewhere in the region). Efforts to restructure ineffective enterprises are blocked, and formally labor compensation costs do not look threatening. In the manufacturing sector, compensations (with payments to the Social Security Fund) do not exceed 17% of product costs. However, we should add costs incurred to preserve jobs, which are almost never taken into account.

2. Narrow wage differentials (especially in the budget sector, where a wage reform is called for, along with the introduction of result-oriented budgeting). The contracted differentials affect the mid- and long-term contribution to future productivity and economic growth in the sectors that are responsible for human capital generation — education and healthcare. Besides, the relatively low return on human capital remains a strong ousting factor.

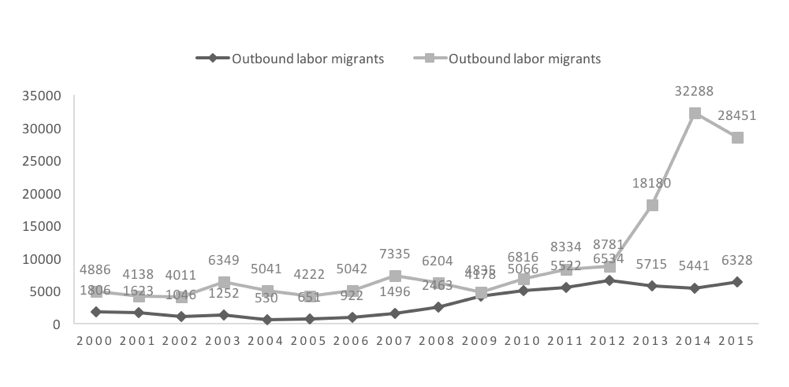

The Palma ratio (the ratio of the richest 10% of the population’s share of GNI divided by the poorest 40%’s share) in Russia has remained more than twice as high as in Belarus in the past decade. Positive migrant selection affects both productivity and GDP due to ‘brain drain.’ This problem becomes evident if we compare the qualification of registered labor migrants who leave Belarus and enter the country.

3. High labor turnover (the turnover rate exceeded 50% in 2010–2015). Workforce is normally reallocated to less productive sectors and is largely motivated by corrupted stimuli to find a less strenuous job. High labor turnover mostly affects the manufacturing sector, which accounts for 32% of dismissed workers and 23% of newly employed workers. In the woodworking sector, the retirement ratio (ratio of dismissed personnel to the average number of listed employees) remained at 38% over the past five years. The lack of balance between professional skills of workers and employers’ requirements is another reason behind the high dismissals rate, along with the overall ineffectiveness of production. The latter forces employers to maintain a fixed share of staff that can easily be replaced (trainees, workers employed subject to a trial period), who are paid minimum wages, in order to be able to pay more valuable staff higher wages. This adaptation mechanism helps enterprises, especially those owned by the state, to deal with excessive employment. This mechanism takes its toll on the quality of workforce, as the share of unskilled workers increases. According to specialists, up to 5% of the employed population (200,000–250,000 people) could be involved in this ‘rotating buffer’ in 2015, and for some sectors the share can be twice if not thrice as high.

4. Slower creation of new jobs, which implies a slower pace of economic modernization. Fewer high-performance jobs were created in 2015 — only 335 job in January–September 2015, down from 690 in 2014.

5. Slow adaptation of the Belarusian labor market to the drop in demand, compared with the rest of the EEU and western countries of the region, which causes insufficient support for the price competitiveness of products (real unit labor costs keep growing).

6. Local labor markets in rural areas and one-company towns were affected the most, and features of ‘spatial’ property traps can be observed there. A recent study5 showed that an increase in wages in a district brings about a reduction of poverty in neighboring districts (growth of prosperity of commuters), whereas the direct negative effect can serve as a signal that low-income population is not involved in the local labor market.

A similar phenomenon can be observed with small business — the existing benefits in small towns and rural areas encourage an increase in the share of workforce involved in business. Because a substantial portion of the workforce in rural areas does not see any motivation to work (which is often aggravated by alcohol abuse), there is a trend towards replacing local workers with from other regions and even from towns (in some cases up to 80% of workers are replaced).

Given the fact that many agricultural organizations remain loss-making, the local community and authorities need to redouble their efforts to prevent poverty traps and deal with the drinking problem. To this end, the Development Program to 2020 includes a target to reduce alcohol consumption per capita to 9.2 liters per year.

In 2015, the situation in the labor market was further affected by general economic challenges, and the country for the first time suffered from a serious deficit of the Social Security Fund (See Table 1). With the continuous ageing of the population and absence of prerequisites for wage hikes, the pension age will definitely be raised.

| Indicator | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSF revenues, BYR bln | 56.995 | 77.910 | 94.403 | 104.785 |

| SSF expenditures, BYR bln | 56.225 | 78.433 | 94.176 | 108.193 |

| Deficit(–), surplus, BYR bln | 0.770 | –0.523 | 0.227 | –3.408 |

| GDP, BYR bln | 530,356 | 649,111 | 778,456 | 869,702 |

| SSF revenues, % GDP | 10.7 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 12.0 |

| SSF expenditures, % GDP | 10.6 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.4 |

| Deficit(–), surplus, % GDP | 0.1 | –0.1 | 0.03 | –0.4 |

| Real GDP growth, % | 1.7 | 1 | 1.7 | –3.9 |

| Growth of employment, % | –1.7 | –0.7 | –0.6 | –1.2 |

| Growth of real wages, % | 21.5 | 16.4 | 1.3 | –3.1 |

| Growth of pensions, end of period, % | –0.7 | 0.5 | 8.2 | 2.3 |

Note. Calculations based on SSF and Belstat data.

No wonder the government started looking for ways to make up for the deficit by cutting ‘grey’ employment schemes. Presidential Decree No. 3 dated 2 April 2015 ‘Concerning the prevention of social parasitism’ envisages annual payments to finance public expenditures by citizens who were not employed or were employed for less than 183 calendar days per year. The annual payment amounts to 20 basic units (USD 181 in 2015; USD 211 in 2016).

According to the official comment, the decree is adopted to “prevent social parasitism, encourage able-bodied citizens to be involved in labor activity, and ensure the compliance with the constitutional obligation to finance state expenditures.”6 It had been planned that the introduction of payments for ‘social parasites’ would become a profitable project, which would contribute some BYR 450 billion to the state budget annually. However, only BYR 5.2 billion was collected during the first year, an estimated 1.1% of the originally planned amount. Since August 2015, only 2,128 Belarusians have admitted to being ‘parasites’, receiving a 10% discount.7

Social protection

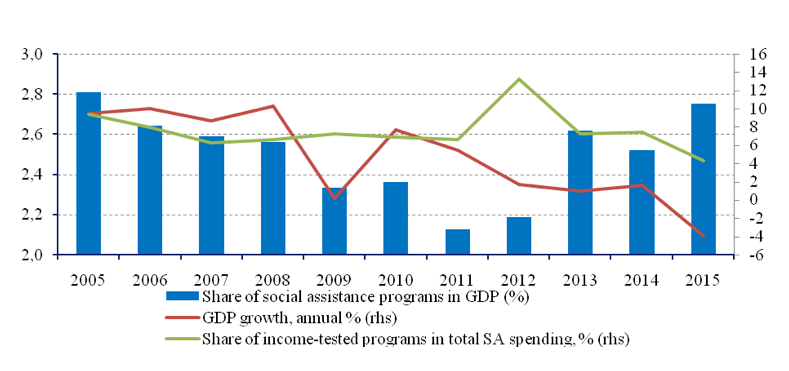

In 2015, the financing of social programs by the state may suggest a counter-cyclic trend: amid the drop in GDP social support grew bigger — to 2.76% of GDP from 2.55% (see Figure 4).

The year 2015 saw a stronger focus of social programs on families with children: families with a child younger than 3 now enjoy a monthly allowance for their other children aged 3 to 18. Given the low effectiveness of state investment programs, the expansion in support for the development of human capital appears to be a more effective and preferable intervention of the state. At the same time, the categories-based approach to social support for families resulted in a serious decrease (up to 4%) in the share of spending on social support, which now calls for testing the real level of incomes.

Moreover, based on disaggregated data on real recipients of social benefits, the efficiency of social support programs is a reason for major concern. The coverage of the population with social protection programs edged down from 76% in 2014 to 75.7% in 2015, meaning that 75.7% of the population fell under at least one of the three social protection programs (social insurance and pensions, labor market, and social protection). At the same time, only 23.9% of the population benefited from state social support programs, 23% from social insurance programs, and 28.8% were entitled to transfers from all of the programs.

Table 2 presents the distribution of beneficiaries by the quantiles of the poorest and wealthiest households. In all types of programs, the presence of the most well-off quantile among recipients increased.

| Type of program | Q1 quantile: 20% least well-off | Q5 quantile: 20% most well-off | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | Δ 2015–2014 | 2014 | 2015 | Δ 2015–2014 | |

| All social support (1 + 2 + 3) | 21.2 | 20.3 | –0.9% | 17.8 | 19.0 | +1.2% |

| 1. Social insurance (all pensions) | 16.5 | 16.0 | –0.5% | 19.9 | 21.4 | +1.5% |

| 2. Unemployment benefit | 58.2 | 58.8 | +0.6% | 3.1 | 6.3 | +3.2% |

| 3. Social assistance, including | 24.7 | 23.3 | –1.4% | 15.6 | 16.6 | +1.0% |

| child allowances | 33.0 | 30.7 | –2.3% | 8.7 | 12.2 | +3.5% |

| other benefits and transfers | 26.2 | 23.5 | –2.7% | 16.1 | 20.9 | +4.8% |

| allowances | 26.6 | 23.2 | –3.4% | 15.6 | 16.3 | +0.7% |

The same applies to targeting accuracy — an increase was reported for the quantile of the most well-off households and corresponding decrease for 20% least well-off households, except for unemployment benefits and allowances (see Table 3). The reduction of coverage was mostly in the segment of the most vulnerable households (from 80% to 72.2%).

| Type of program | Q1 quantile: 20% least well-off | Q5 quantile: 20% most well-off | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | Δ 2015–2014 | 2014 | 2015 | Δ 2015–2014 | |

| All social support (1 + 2 + 3) | 13.1 | 11.9 | –1.2% | 22.5 | 23.8 | +1.3% |

| 1. Social insurance (all pensions) | 9.8 | 9.2 | –0.6% | 24.2 | 25 | +0.8% |

| 2. Unemployment benefit | 49.1 | 49.5 | +0.4% | 7.3 | 9 | +1.7% |

| 3. Social assistance, including | 28.7 | 25 | –3.7% | 14.3 | 18 | +3.7% |

| child allowances | 34.7 | 29.8 | –4.9% | 8.5 | 12.2 | +3.7% |

| other benefits and transfers | 21.7 | 15.6 | –6.1% | 23.2 | 30.2 | +7.0% |

| allowances | 21.5 | 24.5 | +3.0% | 19.5 | 19.3 | –0.2% |

The average poverty rate reached 5.1% in 2015, up from 4.8% in 2014, whereas in rural areas the figures were at 8.7% and 7.9%, respectively. Therefore, the rural population became the category that was most affected by the crisis, the main reasons being the poor situation in agriculture and status of local budgets, which serve as sources of financing of state targeted support and allowances.

The targeted nature of social support programs did not pass the test of the economic downturn. In order to improve the targeted character of social support it is necessary to reduce the share of categories-based payments and introduce tests of real incomes or progressive taxes on transfers depending on the level of household incomes.

Conclusion

Despite the improvement in the demographic situation in 2015, the reduction in workforce and ageing of the employed population remained serious problems. High labor turnover and ‘brain drain’ persist due to low wage differentials. Unit labor costs decrease, but at a lower rate than productivity, which affects competitiveness and impedes the creation of new jobs. An increase in wage differentials appears to be one of very few reserves for encouraging productivity gains. The Belarusian economy may run short of funds to finance social support programs if the recession continues, and wages and employment drop. The deficit of the Social Security Fund makes an increase in the pension age an inevitable move, while the social support system seems inefficient and calls for improvements amid the downturn.