Labor Market: A ‘hostage’ of low profitability

Uladzimir Valetka

Summary

In 2014, the natural population decline was further reduced in Belarus, and the total population increased, primarily due to an increase in net migration rate. However, in the medium term, there are no prerequisites for labor productivity to increase, the main reason being the country’s ineffective manufacturing sector and persistent structural problems in the labor market.

The potential for creating new productive jobs remains low in the context of the ineffective labor market. Because external markets narrow and ineffectiveness of production accumulates, efforts to cut labor costs alone without restructuring moves are not enough to boost competitiveness. Social security agencies are designed to operate in a full employment model, which hampers the development of a dynamic labor market that is necessary to increase the competitiveness of the national economy.

Trends:

- Reduction in workforce and ageing of the employed population;

- Slower creation of new jobs;

- High labor turnover and ‘brain drain’ that impede productivity growth;

- Failure of social security agencies to meet labor market requirements;

- Limitations on wage increases, which are nevertheless insufficient to increase competitiveness.

Demography

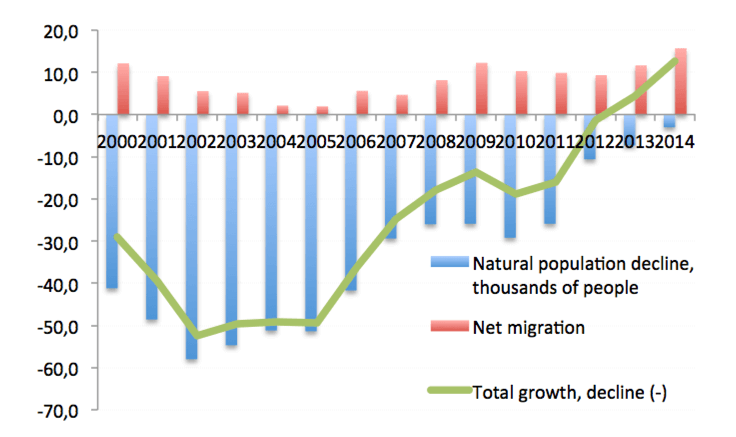

In 2014, the natural population decline declined by 59% from the level reported for 2013 to 3,000 people (Figure 1). Due to the increase in the net migration rate, Belarus’s population reached 9,480,900 people at the end of 2014, up from 9,468,200 at the start of the year. Net migration amounted to 15,700 people in 2014, including 13,900 people from the CIS (89%). Last year’s increase was for the most part due to migrants coming from Ukraine.

Despite the registered net migration, population decreased in four out of six Belarusian regions, and only the Brest Region and the city of Minsk reported increases in population. The capital city saw its population increase by 16,600 people, slightly more than in 2013.

In 2014, 118,500 babies were born in Belarus. Despite the fact that since 2013, child care allowances provided to families with children younger than three years of age have been pegged to the average wage of one parent (which resulted in a substantial increase in expenditures of the Social Security Fund) the birth rate increased only by 0.5% year-on-year, much slower than in previous years (1.8% in 2013 and 6.2% in 2012).

On 1 January 2015, the five-year Big Family project was kicked off in Belarus – the initiative is financed from the increase in the income tax rate from 12% to 13%.1 As part of the program, USD 10,000 will be credited to a deposit account of a family, where a third and subsequent child is born; however, the money can only be used once the child turns 18.

The number of marriages dropped by 3.7% year-on-year in 2014, and the number of divorces decreased by 3.4%. The ratio of marriages to divorces reached 1,000 to 415, which compares to 1,000 to 414 in 2013.2

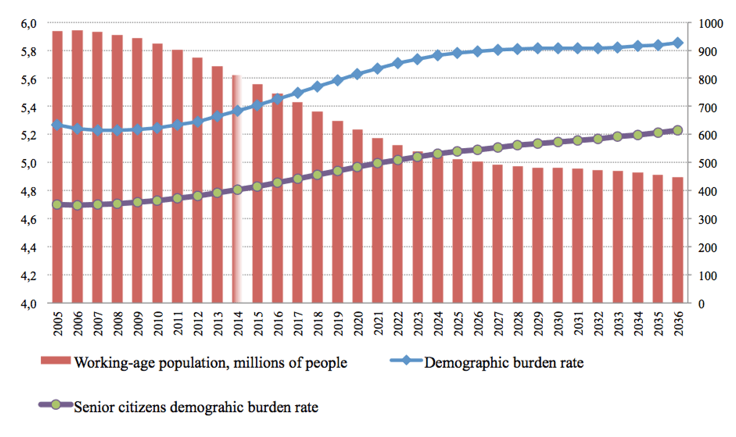

In 2014, all of the objectives of the Demographic Safety Program for 2011–2015 were achieved. However, Belarus’s workforce has been falling (Figure 2) – by 63,000 people in 2014 (following the decrease by 64,000 people in 2013).

The gradual reduction in the working-age population is due to demographic factors, which were analyzed in detail in previous Belarus Yearbook issues.3 According to forecasts, Belarus will have 4,895,400 working-age citizens by 2036, or 51.9% of the total population (the share was at 58.6% in early 2015). The increase in the proportion of people younger than the working age will end in 2023.4

Therefore, despite certain progress in the country’s demographic policy in 2014, during the next two decades, the share of working-age population will be decreasing amid the growing share of the population older than the working age (according to current standards, 60 years for men and 55 years for women).

Employment and unemployment

While demographic parameters of economic growth are very important, the above results of the country’s demographic policy are extensive and require long-term investments as soon as possible,5 although they do not guarantee an increase in the intensity of available and future labor resources. Labor market institutions must create preconditions for increases in productivity, primarily through promoting the quality of human capital.

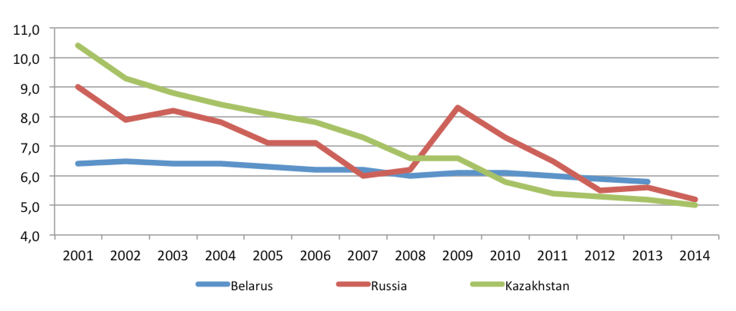

At the same time, statistics show that the Belarusian economic institutions fail to make full use of available labor resources. This is evidenced by the situation in foreign economies. According to available data, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) countries have similar levels of economic activity and unemployment. At the same time, according to ILO estimates, Belarus’s labor market utilizes less capacity than Kazakhstan and Russia,6 because unemployment falls slower in Belarus than in its EEU partners (Figure 3).

Source: Author’s calculations based upon data for 2001–2013, see http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS; for 2014 – sample surveys of population concerning employment issues.

The balance of labor resources in Belarus also suggests that the economy mostly suffers from inefficient employment and poor quality of resources, rather than quantitative limitations of labor supply (Table 1). In 2014, the number of employed citizens edged down by 1.3% year-on-year, or by 59,000 people, to 4,486,700 people. The unemployment level remains unchanged, though – because of the concentration of resources in the public sector, including credit resources, the private sector is chronically short of resources to create new jobs.

Although formally the share of workforce employed in the private sector increased – to 58% in 2014 from 54% in 2010 and 56.5% in 20138 – this happens due to the growing number of employees of private companies with state interests – to 26.1% in 2014 from 20.3% in 2010 and 25.5% in 2013. This corresponds to the increase in state assets. According to the State Property Committee, the state supported 111 open joint-stock companies of ‘republican ownership’ in 2011, whereas in 2013, there were 279 such companies. In exchange for support, BYR 2.3 trillion worth of shares were transferred to the state in 2014 alone (5.5% of the total trading at the stock exchange).

| Indicator | 2012 | 2013 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| thousands of people | % | thousands of people | % | |

| Workforce, total | 6,030.4 | 100.0 | 5,989.10 | 100.0 |

| Including: | ||||

| – employed population | 4,577.1 | 75.9 | 4,545.6 | 75.9 |

| – other working-age population, including: | 1,452.9 | 24.1 | 1,443.5 | 24.1 |

| unemployed, registered at labor, employment and social security agencies | 28.5 | 0.5 | 23.4 | 0.4 |

| persons without work who actively seek work and are ready to start working (unemployed defined by the ILO) | 211.1 | 3.5 | 212.2 | 3.5 |

| persons on maternity or childcare leave (for children younger than three years of age) | 272.5 | 4.5 | 297.3 | 5.0 |

| persons receiving training at educational institutions who do not combine studies with work | 497.4 | 8.2 | 457.7 | 7.6 |

| persons entitled to allowance to care for a disabled child, disabled person of group I or a person older than 80 years of age | 58.3 | 1.0 | 59.1 | 1.0 |

| persons staying at correctional and detention facilities | 16.2 | 0.3 | 14.6 | 0.2 |

| citizens of the Republic of Belarus working abroad | 55.4 | 0.9 | 63.4 | 1.1 |

| homemakers | 130.8 | 2.2 | 123.6 | 2.1 |

| persons who believe that there is no possibility for them to find employment | 42.0 | 0.7 | 37.1 | 0.6 |

| persons who do not need or want to work | 30.2 | 0.5 | 29.7 | 0.5 |

| other | 110.5 | 1.8 | 125.4 | 2.1 |

Source: Author’s calculations based upon labor balance data.

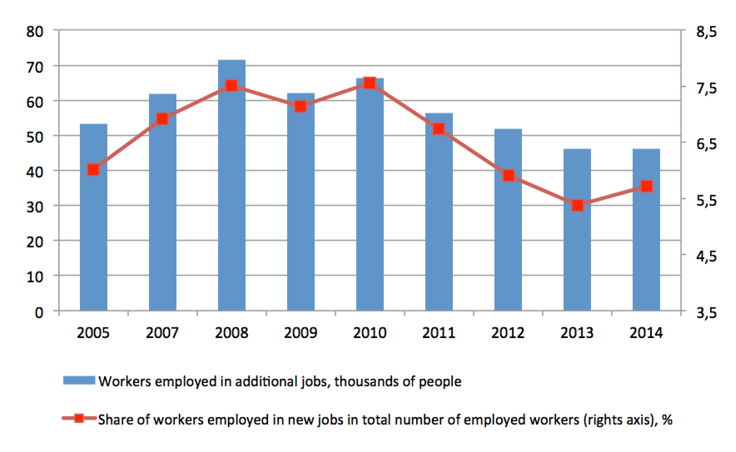

Amid high labor turnover, new jobs are created very slowly. In 2014, only 690 workers were employed or transferred to newly created high-performance jobs that appeared as a result of investment projects (290 workers were transferred). However, these new jobs are naturally created in specific industries and locations – 84% of newly employed workers found jobs in the Homiel Region, and 47% of them were employed in the metals industry. Overall, fewer new jobs were created in 2014 than in previous years (Figure 4), which implies that economic modernization has slowed.

Transfer of workforce to new jobs in sectors with higher productivity is a very slow process, whereas labor turnover remains quite high (in 2014, labor turnover ratio exceeded 53%). Transfer of workforce is largely motivated by distorted stimuli (search for less tense working environment, especially in the public sector, where there is hardly any pay differentials). High labor turnover can also be attributed to seasonal workforce flows, which is also characteristic of the public sector.

There are reasons to believe that labor migrants account for a substantial portion of active workers with high productivity. Labor migration reduces supply in the domestic labor market; therefore, the number of applications to job centers for employment assistance decreases faster than the number of vacancies grows.9

In 2013, 257,000 people applied for employment assistance, down by 11.5% year-on-year, and in 2014, 231,100 people sought employment assistance. In 2013, job centers helped 182,100 citizens (including 121,000 jobless persons) to find employment, and in 2014, respective figures dropped to 159,600 and 108,600.

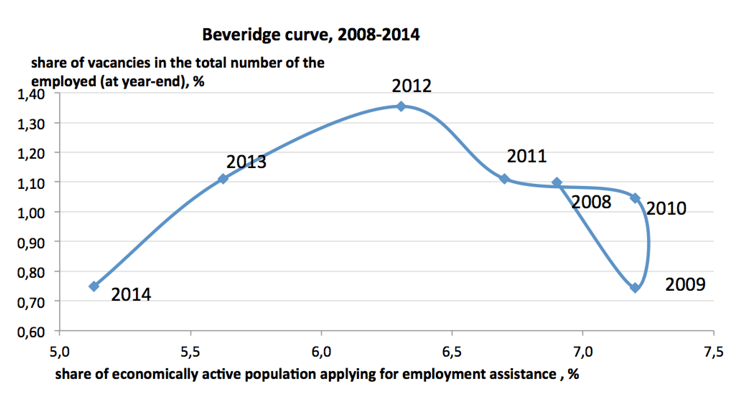

In 2014, the so-called Beveridge curve indicated a change from the negative slope (more vacancies – less employment) to the positive slope and dropped to the pre-crisis job vacancy level observed in 2009 (Figure 5). Last year’s job vacancy gap with the trend recorded in 2010–2012 reached approximately 65%, i. e. the national labor market provided only a third of expected employment – 33,600 vacancies instead of 95,000 (2.1% out of 4,569,000 economically active persons).

Source: Author’s calculations

Source: Author’s calculations

Official unemployment remains quite low. As of the end of 2014, there were 24,200 unemployed Belarusians, 0.5% of the country’s workforce (which compares to 20,900 jobless citizens at the end of 2013). As of 1 January 2015, males accounted for more than half of all unemployed citizens (62.4%, up from 59.4% on 1 January 2014), and young people aged from 16 to 29 accounted for 30.1% (down from 34.6% at the start of 2014). The share of the unemployed with higher education remained at 11%.10

The consequences of economic problems and the campaign to detect ‘social parasites’ showed their first results at the very start of 2015 – by late January, the number of jobless Belarusians had increased to 30,700 people, an increase by 35% from late January 2014 and by 26.8% from late December 2014. Official unemployment rate increased to 0.7% of Belarus’s workforce at the end of January 2015.

In January 2015, the average unemployment allowance stood at BYR 182,400 (2.4% of the average wage, or 12.8% of the minimum subsistence wage per capita). Low allowances are the main reason why employers do not regard job centers as an institution capable of offering high quality workforce and facilitate restructuring of the national economy.

Therefore, labor market institutions traditionally perform the functions of maintaining and equalizing incomes, rather than encouraging highly productive employment and economic restructuring. As a result, Belarus remains in a trap of equal incomes, as efforts to increase wages have no desired results (preservation of workforce capacity), because of the ousting factor – relatively lower return on human capital. Migration slows productivity increases and GDP growth because of ‘brain drain.’ Narrow wage differentials minimize medium- and long-term contributions to future productivity and economic growth in the public sector (most of all education and healthcare).

Ineffective labor market as a threat to economic competitiveness

A stable but ineffective labor market always produces a negative impact on an economy. It is no coincidence that return on investments has been decreasing in Belarus for a decade now.11 Reverse incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR) dropped from 0.45% in 2004 to 0.03% in 2013 (less than 0.2% on average in 2005–2013, and ‘increased’ to 0.04% in 2014). This can largely be attributed to the characteristics of the country’s uncompetitive capital market, which determines sector-wise investment structure (dominance of the state banking sector; weak securities market; redistribution of investments via state programs, specifically preferential home lending, only ensures long-term return on capital, which ‘freezes’ capital). As long as the government fails to apply market mechanisms to the selection of projects when approving state programs, the country will face a situation where additional investments will be required to produce an additional value added unit.

A recent study12 has showed that other reasons have remained decisive for the past decade. The low return on capital is attributable to the established market hierarchy, which reflects the current economic policy – the capital market is ‘subordinate’ to the labor market,13 which is not dynamic enough for capital to effectively flow to sectors generating higher value added.

The distorted market logic leads to a series of structural problems. The lenient fiscal policy, which is justified by fears of dismissals and unemployment, slows the restructuring process. Privatization only changes the legal form of state enterprises without creating new property rights or encouraging effective corporate governance. State companies and industry institutions lobby channels of noncompetitive privileged access to capital. This practice cements the dominance of state banks as chief players of the financial market and source of investments and results in high capital costs for private companies. In exchange for access to capital state enterprises and industry institutions agree to maintain excess employment and administrative wage targeting, which distorts functional distribution of incomes – the share of labor incomes in GDP is growing despite external market contractions.

All other conditions being equal, the relative increase in wage rates implies that people generating income from selling their labor will have larger amounts of incomes than capital owners. This discourages investment in the economy, which further slows the introduction of new solutions and modernization of work sites that are required for productivity gain. Further growth in wages and savings will be volatile as long as productivity remains unchanged, and accumulations will be growing faster than savings (a resource gap), which leads to an expansion in foreign debt and balance of payment deficit.

The said factors create a new institutional trap: lower return on investments discourages investors’ demand for effective financial institutions and creates preconditions for capital outflows. This might slow the diversification of the national economy and increase imbalances. Therefore, more effective labor and capital markets are required for Belarus to achieve sustainable growth. This challenge should be high on the agenda for complex structural reforms aimed to improve the allocation of resources.

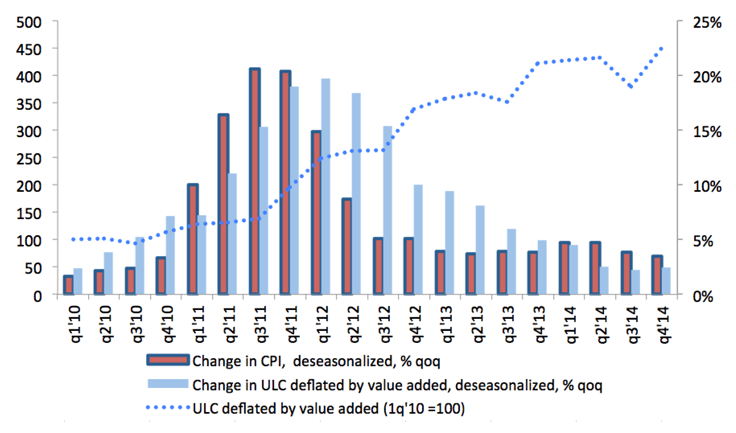

Because of excessive employment and the fact that wage targeting has gained momentum, unit labor costs in Belarus appear to be higher than elsewhere in the Eurasian Economic Community. The same applies to labor taxes (transfers of portions of wages to the Social Security Fund). Now that the Belarusian economy is faced with a new challenge of narrowed external markets (especially in Russia), the country will have to tackle ‘internal devaluation’. In the second half of 2012, certain features of this devaluation became apparent: wage growth slowed, underemployment went up, and the number of workers made redundant doubled. In 2014, the trend further enhanced: real disposable incomes of the population went up by only 0.1% year-on-year, and real wages increased by 0.3%. Despite the reduction in nominal unit labor costs (ULC)14 deflated by the GDP deflator in January–September 2014, the slower increase in wages renders efforts to recover the competitiveness of the national economy ineffective. Similar conclusions can be drawn about ULC deflated by value added – a reduction in unit costs could only be observed in the third quarter of 2014 (during the previous 15 quarters – from the fourth quarter of 2010 to the second quarter of 2014 – unit costs decreased only in the third quarter of 2013).

A positive result of this trend is that the inflation pressure of wages decreased in 2014, despite the fact that in the fourth quarter of 2014, ULC growth resumed. Deseasonalized change in ULC remained in positive territory (Figure 6), which correlates with the downward nominal wage rigidity in the Eurozone.

Source: Author’s calculations

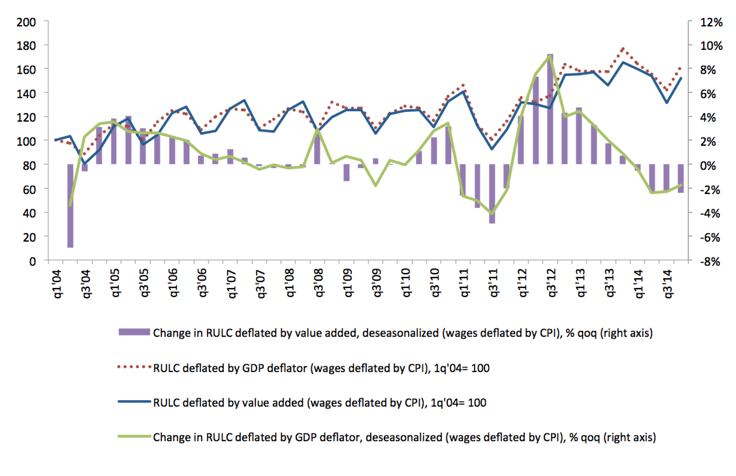

Analysis of real ULC (RULC) conducted in the process of calculating real wages (deflated by the GDP deflator) shows that deseasonalized RULC change remained in negative territory during the last three quarters of 2014. To forecast the possible impact of RULC reduction on the profitability of export, changes in real wages based upon CPI should be assessed (CPI better accounts for the increase in prices of traded products than the GDP deflator). According to our calculations (Figure 7), in 2014, RULC did decrease in 2014 if real wages are calculated based upon CPI, albeit moderately.

Source: Author’s calculations

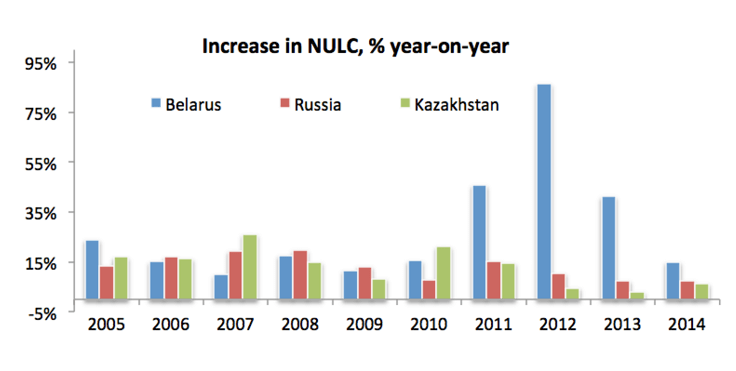

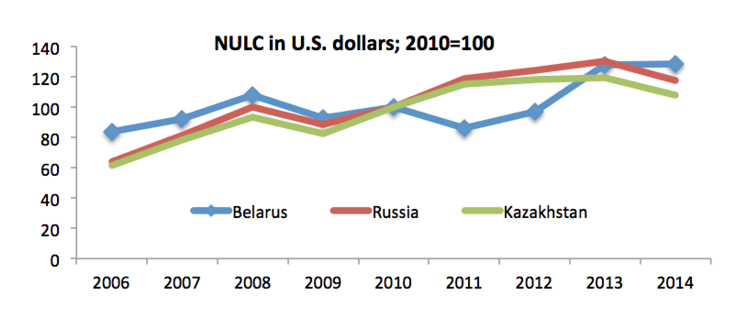

In these context, it becomes a real challenge to maintain the competitiveness of the Belarusian economy even at the level of the other EEU member-states – its labor market is less flexible and has less capacity to adapt to the recession than the labor markets of the EEU partners – ULC decrease slower (Figure 8), whereas changes in ULC in U.S. dollar terms (Figure 9) make it increasingly harder to maintain the volume of export. In 2014, as in 2009, unit labor costs were falling faster in Russia and Kazakhstan.

Source: Author’s calculations

Source: Author’s calculations

The problem of the country’s competitiveness is determined by the overall efficiency level and high material consumption of Belarusian production facilities. Organizations manufacturing machines and equipment account for the biggest portion of unsold inventories (23.3%). In 2013, the share of wage costs and transfers in production of machines and equipment accounted for 23% of total costs, compared to 16.7% for the entire industrial sector. As a result, in order to apply exclusively internal devaluation instruments and produce the same impact on the economy as a 10% ruble devaluation, wages (or employment) in organizations making machines and equipment need to be reduced by 40%. In conditions of high import consumption of Belarusian production facilities, devaluation of the national currency leads to simultaneous ‘inflation import’ – 1% devaluation brings about an increase in inflation rate by approximately 0.4 of a percentage point, which in the new production cycle automatically ‘neutralizes’ 25% to 30% of the decrease in export prices denominated in foreign exchange. Therefore, increasing competitiveness appears to be an impossible task without putting in place fundamental structural reforms.

The current scope and overall capacity of internal devaluation in Belarus are insufficient for restoring the competitiveness of the Belarusian economy. In order to balance the reduction in purchasing power and prevent significant decreases in medium term growth, ‘internal devaluation’ is a useless policy, unless additional steps are taken to restructure enterprises and introduce structural reforms.15

Conclusion

The persistent structural problems in the labor market make it impossible to rely on human capital for a larger contribution to economic growth in the medium term. Decades of wage targeting policy have brought about increases in labor costs and slowed the creation of new highly productive jobs. The habit of living beyond means and distributing investments behind closed doors is hard to kick fast. Anyway, the capacity of internal devaluation without restructuring of enterprises and introducing structural reforms will not suffice to restore the competitiveness of the national economy. To maintain competitiveness, a dynamic labor market is required with corresponding social security institutions; however, this is something that Belarus does not have.