Media: Lost control and destroyed infrastructure

Elena Artiomenko-Meliantsova

Summary

Potential threats to information security and media management inadequacies manifested themselves to the full extent in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and the political crisis that followed the August 9 presidential election revealed the incapacity of outdated approaches to media management.

The government’s response to the challenges posed to the media exacerbated the situation, and even led to the loss of sovereignty in the information area (when Russian specialists were invited to state TV channels) and the destruction of independent media infrastructure. As a result, the polarization of the information space and public views increased, and conflicting narratives emerged in the communications space. There is no room left in the country for unbiased journalism and balanced coverage of social and political events.

Trends:

- State-controlled media lose confidence of the protest-minded part of society;

- New media are used to amplify hate language;

- Unprecedented repression is applied against independent journalists;

- Information security infrastructure is destroyed.

Media in the context of major nationwide events

The 2020 events not only affected the media landscape in Belarus, but also entailed fundamental changes in the relationship between the media, society and the state, as the latter lost control over the media scene, and information security infrastructure was destroyed.

According to many experts, the authorities’ strategy on the COVID-19 pandemic coverage undermined credibility of the state media, while Belarus’ pandemic response measures were the most lukewarm in the region. During the first wave of the pandemic, the official media primarily aimed at preventing a panic. Instead of the fullest possible awareness building and safety measures, top officials downplayed the seriousness of the problem and disease after-effects, and statistics was heavily redacted to be nearly incomprehensible.

Information about the COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates was published irregularly; no region-wise comparative figures were provided; and many health professionals with knowledge of the matter dismissed the published figures as inaccurate. Eventually, the data provided were no longer credible to the public, since they did not match the overall global trends.

Since mid-April, representatives of the Health Ministry stopped answering reporters’ questions about the morbidity rate during regular briefings, and only posted press releases, although the Belarusian Association of Journalists seconded by tut.by, BelaPAN newswire and Naviny.by released in late March a request for exhaustive information about the spread of COVID-19. Access to reliable information about the situation got even poorer after that.1

According to the authors of the COVID-19 Disinformation Response Index report,2 President Lukashenko along with Russian publications were the main sources of false data on the pandemic. Among the misinformation narratives, the report highlighted the downplaying of the danger of the disease, coverage of the pandemic in the context of the geopolitical confrontation between the United States and China, and numerous rumors about the severity of the situation in Belarusian cities. The cumulative COVID-19 disinformation response index of Belarus was lower than that of all other countries named in the report (Eastern Partnership members and Romania). Belarus only scored 1 point in the disinformation response by (a) the state, (b) the media, and (c) society each, i.e. a total of 3 points out of 8.4 points (the Eastern Partnership average) and 9.0 points (Romania).

Independent media were subjected to repression for their attempts to advocate more substantial anti-COVID-19 measures and for voicing concern over the situation. The Belarusian president publicly called for combating independent media, accusing them of “stirring up a psychosis” and “throwing in fakes.” Reporters Without Borders believed that criminal charges against Yezhednevnik Editor Sergei Satsuk were pressed for the criticism of the authorities’ response to the pandemic. Officially, he was charged with bribery. Satsuk was released from custody, but the charges have not been dropped.3

The administrative case against Media-Polesye portal, which informed about a patient’s death, is another example of repression against media for pandemic-related reports. The Ministry of Information called this information unreliable and detrimental to the state. Despite a prompt correction, an administrative case was brought against the portal under section 22.9.3-1 of the Administrative Offences Code (dissemination by a media outlet of information prohibited from publication in media). According to the Belarusian Association of Journalists, that was the first case when section 22.9.3-1 (added to the Code in 2018) was applied.4

The presidential election campaign in Belarus was much more intensive than the previous ones. Opposition candidates, including those who can be considered present or former part of the power elites and political establishment (Viktor Babariko and Valery Tsepkalo) were very active; political technologies with elements of performance art events (Sergei Tikhanovsky) were applied; massive information campaigns of the candidates were conducted on the Internet, including on YouTube and social media. Voters showed unprecedented activism in many respects caused by anxiety, frustration and discontent with the authorities’ rhetoric about the pandemic.

In terms of the electoral behavior, the campaign was accompanied by mass rallies and actions of solidarity with victims of repression, activism of volunteers at candidates’ election headquarters, and the unprecedentedly large number of signatures collected for the nomination of the candidates that acted as an alternative to the incumbent president. The regions also showed a high degree of political mobilization.

Independent media actively covered the campaign and supported the alternative candidates. Repressions against independent journalists grew in momentum during the election campaign: from May 8 to August 9, the Association of Journalists registered 23 violations of journalists’ rights.

Mass protests against the election rigging began right after the official result was reported. Following the crackdown on protesters, Belarusians began to protest against police brutality as well. The mass rallies of August-September 2020 were huge as never before; the regions were active more than ever, and so was the severity of repression, including against the independent media and the mass media as a whole.

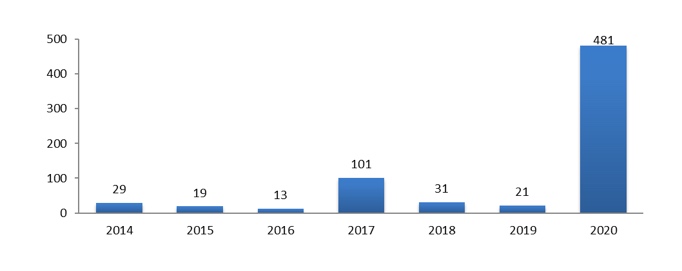

As many as 481 detentions of journalists were reported in 2020, which is almost three times more than during the 2011 protests (Figure 1). It is also important to note the use of force: violence during arrests and detentions was reported by 57 journalists; firearms were used in three episodes.5

Source: Belarusian Association of Journalists

Journalists were also subjected to criminal prosecution. According to the Association of Journalists, in 2020, criminal cases were initiated against 15 media representatives, including Belsat journalists Ekaterina Andreyeva and Daria Chultsova, tut.by journalist Ekaterina Borisevich (disclosure of privileged medical information), and heads and employees of the Press Club.

Many journalists of foreign periodicals were denied accreditation, and representatives of foreign media, who worked in Belarus during the election campaign, were stripped of accreditation. Independent media websites were blocked in circumvention of the legal procedure. As of late August, the Information Ministry restricted access to more than 70 websites. The country’s largest news portal tut.by lost its status of a media outlet. State printing houses refused to print independent newspapers Narodnaya Volya, Komsomolskaya Pravda v Belarusi, Svobodnye Novosti Plus, and BelGazeta, and their issues printed abroad were not accepted for distribution through the networks of Belposhta and Belsayuzdruk postal operators.6

Loss of trust and polarization of the information space

Authorities’ efforts to influence public opinion and ensure information security under the above circumstances produced poor results and often led to an opposite effect. In general, state-controlled media were losing credibility, and the central government was losing control over the media space.

According to a representative opinion poll by the Eastern Neighborhood of the European Union, in 2017, 36% of the population used traditional media alone as a source of information, 52% used the Internet and social media, and 12% generally did not use any media to obtain information.7 In 2020, these proportions made up 34%, 52% and 14%, respectively.8

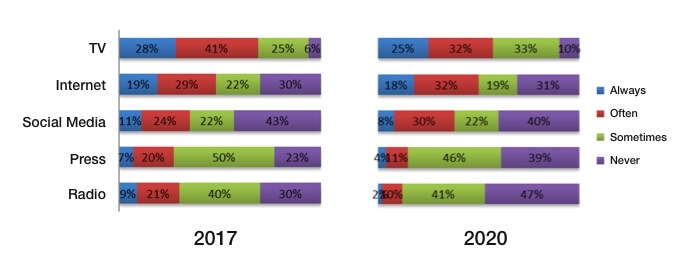

In 2017, television was a source of information (always or often) for 69% of respondents to compare with 58% in 2020; 48% obtained information online against 50% in 2020 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Answers to the question, “How often do you use the following media as a source of information?”, 2017 vs 2020

Source: EU Eastern Neighborhood

This shows that the consumption of media content did not fundamentally change. However, the share of those who watch television is steadily decreasing, although it still constitutes more than a half of the audience. The share of those who only use traditional media is decreasing, and it is currently around one-third of households.

Following the 2020 events in Belarus, the share of active Internet users (data of opinion polls conducted online can be extended to this group) show little trust in the state-controlled media. According to the Chatham House’s online survey, 16% of respondents trust state-controlled media, while 50% trust independent periodicals. It is also noteworthy that the survey primarily targeted at the opposition-minded electorate: 24% trusted the incumbent president, 43% trusted Viktor Babariko’s headquarters, and 39% trusted Svetlana Tikhanovskaya’s team.9

The decline of trust in traditional state media and increased demand for up-to-date information is indirectly indicated by active growth of popularity of Telegram news channels. According to the statistics on the Belarusian segment of Telegram, the audience of the largest channels averaged 1.3 million subscribers a year (1.8 million at the peaks). A part of the subscribers could be foreigners, but they definitely do not constitute a majority (Table 1).

| Link | Average annual number of subscribers | |

|---|---|---|

| NEXTA Live | @nexta_live | 1,300,000 |

| NEXTA | @nexta_tv | 626,400 |

| Tut.by news | @tutby_official | 404,800 |

| Belarus of the Brain | @belamova | 278,900 |

| Tea with Raspberry Jam | @belteanews | 163,300 |

| LUXTA | @luxta_tv | 149,400 |

| My Country Belarus | @mkbelarus | 142,000 |

| Typical Belarus | @tpbela | 139,300 |

| Onliner | @onlinerby | 137,100 |

| MotolkoHelp | @motolkohelp | 134,900 |

Table 1. Popular Telegram channels and their subscribers, 2020

Source: by.tgstat.com

In 2020, state media were fiercely attacking supporters of the protests, and, therefore, largely lost their credibility among those who obtain information from alternative sources. According to a scientifically based approach to changing public opinion, promotion of attitudes that radically differ from the audience’s perceptions leads to a consolidation of the audience’s opinion and even repudiation, i. e. larger dismissal of the ideas meant to be implanted. The state media chose the strategy of counterbalancing independent communication channels with aggressive rhetoric, including through new media channels, such as paid online advertising (instream advertising on YouTube, etc.). As a result, the media agenda and public opinion became polarized, and a tangible lack of media with well-thought-out, unbiased information policy was observed.

Due to the erupted social conflict and the firing of some state media employees, Russian media professionals were invited to the country. After that, the rhetoric of the state media became even harsher, and new guest experts began to show up. The protests in Belarus began to be compared with the events in Ukraine in 2014 and it was insistently claimed that Western intelligence services were interfering in Belarus’ internal processes. The skyrocketing popularity of Telegram channels and media outlets that broadcast from outside the country, as well as the work of Russian journalists on the Belarusian TV testify to the loss of information sovereignty and significant undermining of information security.

Degradation of media infrastructure

Repressions against the Press Club, increasing complexity of the registration of humanitarian aid, and the narrower framework established for foreign charity programs limit the possibilities for professional development and competence building in the field of Belarusian journalism and media management, which can be considered a threat to media infrastructure.

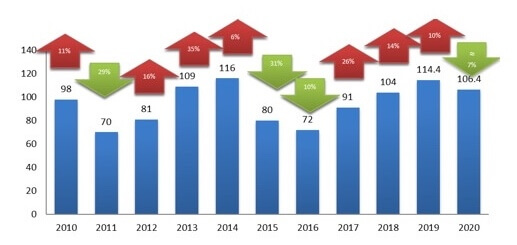

The deteriorated economic situation and the acute political crisis also could not but affect media infrastructure. An optimistic forecast for 2019 assumed 8% growth of the advertising market. However, the October 2020 estimate shows that the advertising market may shrink by 7%, primarily because of the decline in traditional media (down 7% on TV, 15% on radio, and 30% in the printed press) (Figure 3).10

Figure 3. Dynamics of advertising in the media market, 2011–2020, USD million

Source: WebExpert, Alcazar.

The situation was also affected by the political crisis. In August 2020, some major advertisers reduced their presence on state TV channels. Online advertising volume in Belarusian rubles changed insignificantly: investment in online advertising rose by 3% in October, and by 2% in contextual advertising, although considerable growth was expected in the 2019 forecast.

In addition to insignificant growth of investment in online advertising, government agencies restricted the free distribution of information on the Internet in order to prevent mass protests. In the first week after the August 9 election, the Internet was shut down on the days of mass rallies, and some Internet services were slowed down and/or suspended, which can also be regarded as undermining of information infrastructure.

Conclusion

In response to the 2020 events (the pandemic, election campaign and post-election protests), Belarusian authorities chose a strategy of limiting access to information, pushing out and suppressing independent media and severest on-record repressions against journalists. This strategy polarized public opinion and compromised information security. It is fair to say that the country’s leadership lost control over the information space in 2020. The measures taken and the rhetoric chosen give no reason to hope that this control will be re-established, and that state-controlled media will regain credibility among the protest-minded part of the population.

The year 2021 is likely to see a further decrease in the funding of state and independent media due to the economic recession and obstacles posed to international technical and financial assistance.