Labor Market Contraction

Vladimir Akulich

Summary

The ageing of the population, emigration of workforce, complicated administration and significant expenses associated with the hiring of foreigners reduce supply in the labor market. A decline in the working-age population and, accordingly, in the number of the employed is becoming a factor that constrains economic growth and opportunities for preventing stagnation.

Trends:

- Decrease in population, increase in workforce migration and the share of people of retirement age;

- Growing workforce shortages;

- Lowest wages in the region against the backdrop of considerably increased wages and unit labor costs that outstrip labor productivity.

Population and workforce

Belarus’ population continues to decline. Over the past three decades, the population decline rate reached 8.0% (781,000 people): 24% in the 1990s, 64.0% in the 2000s and 12.0% in the 2010s, which means that the decline has slowed down.

According to the most recent census, Belarus’ population totaled 9,413,000 people as of October 4, 2019. The natural decline in the population continued: minus 33,000 people in 2019 to the psychological milestone of 9,408,400 as of the end of 2019.

Belarus remains almost the most sparsely populated country in Europe (129th in the world in terms of population density). Apart from Minsk, which accounts for 0.3% of the total area of the country, the population density in the remaining territory stands at 35 people per km2 (139th in the world). For comparison, with such density in neighboring Poland, Belarus would number 25 million people.

President Lukashenko said in 2017 that 20 million would be the ideal population size for Belarus, at least 15 million would be OK for starters.1 However, despite all incentives aimed at stimulating the birth rate, the number of children born in 2019 was minimal since the end of the World War II.

Over the past three years, the number of newborns decreased by 25% to 87,600 in 2019 against 117,800 in 2016 basically due to a decrease in the number of women in their childbearing years, especially in rural areas. The age-specific birth rates declined, but they are still higher compared with the 1990s and 2000s in all age groups, except for urban women aged 20 to 24.

The natural (for a highly urbanized country) ageing of the population is exacerbated by the outflow of the youth. This leads to a decrease in the working-age population (5.3 million in 2019 against 5.8 million in 2009). The situation is smoothed somewhatby the ongoing gradual increase in the retirement age, as well as the high rate of employment of the working-age population, which rose in recent years (80.9% in 2016; 83.4% in 2019).

Around 1.4 million people of employable age stay beyond the national labor market. This includes home keepers (98,000 in 2018) and Belarusian nationals employed outside the country (127,000 in 2018). At the same time, 0.4 million people at the age below and above the employable age are present on the labor market. In 2019, Belarus numbered 4.3 million people employed in the national economy (4.6 million in 2009).

The government is trying to compensate the decrease in the number of the employed by increasing the share of the employed working age population. Decree No. 3 ‘On Prevention of Social Parasitism’ (2015) pursued this particular goal. “At least 300,000 people who do not work today must be forced to work,” the president said.2

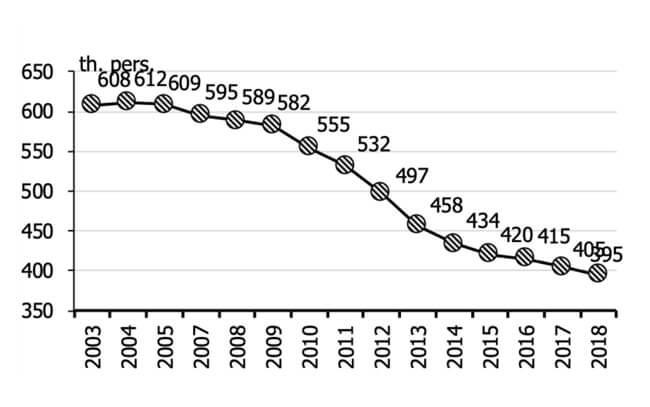

The number of working-age students without side jobs has decreased by one-third over the past 15 years from 612,000 (100 per 1,000 working-age population) in 2004 to 395,000 (70 per 1,000) in 2018 (see Figure 1).

Every year, the Labor Ministry conducts research to find out the trades in demand in the domestic market and then, based on the findings, the Education Ministry determines the sizes of enrolment. Given the economic stagnation of the past decade, which turns into a recession once in a while, and the increasing share of raw materials and low-tech goods in national output, demand for workforce mirrors these processes. Enrolment targets tend to decrease, especially in universities.

Private universities continue to be closed. The law on deferments issued in 2019 reduced the number of deferments from military service, which may be granted to a university student for uninterrupted education, to just one.

Attempts to stimulate the birth rate wash out a significant part of the workforce from the market, as the country has one of the world’s longest parental leave terms (3 years). There were 148,000 people on parental leave on average in 2005, and their number reached 345,000 in 2016–2019 (99% of them were women). According to BEROC Economic Research Center, “a reduction in the parental leave by one year can increase GDP by 1.3% through a direct increase in employment, and another 1.4% through the preservation of the human capital of those on leave.”3

Employment

Belarus’ GDP depends not only on investment and factor productivity, but also on the number of the employed. This number reached an all-time low of 4,330,000 in 2019. Enterprises fired 736,000 people and hired 690,000 (minus 46,000). The layoffs were mainly observed in the production sector. The number of workers decreased by 19,000 people (on a net basis) in the industrial sector, by 11,000 in agriculture, and by 6,000 in construction. Some trades in the service sector thus showed a certain increase. IT companies reported an increase by 4,000 workers, healthcare by 600 and trade by 500.4

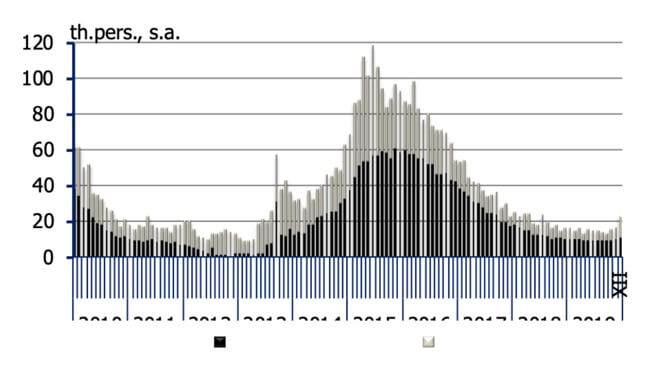

The dynamics of the number of part-time employees and/or those placed on leave by employers indicates that the labor market has recovered after the 2014–2016 recession (Figure 2). Therefore, the decline in employment cannot be attributed to the weakness of the economy. This is rather about the shrinking demographics and insufficient flexibility when it comes to taking measures to overcome this situation, first of all the hiring of foreign workers.

Amendments to the law on external labor migration were made in 2016 to protect the domestic labor market during a recession. According to the law, employers must make contributions to the Social Protection Fund for each foreign worker, provide medical insurance, and obtain the Labor Ministry’s permission to hire a foreign worker, if the work cannot be performed by a Belarusian national. The recession ended, but the restrictions remained in force.

20,800 foreigners were hired in Belarus in 2019 (up 13% from 2018). According to the Russian Ministry of the Interior, 163,400 Belarusians found jobs in Russia (a 21% year-on-year increase). Eurostat reported that over 100,000 Belarusians were employed in the EU, while Belstat reported 127,000 Belarusians employed there in 2018 (up 3-fold from 2015).

The balance of payments data also indicates that the outflow of labor force from Belarus is increasing. In 2019, those employed outside the country transferred USD 490 million to Belarus (up 11% from 2016). Labor migrants were paid USD 448 million in wages (up 43% from 2016).

Head of the Labor Ministry’s Employment Policy Department Oleg Tokun said that “in 2016-2017, the situation dictated the need to set a limit on the employment of foreigners to protect the rights of Belarusian citizens.”5 He said the situation had changed, though. “As demand for workforce is growing, and the number of the unemployed is reducing, perhaps, we could relax the restrictions on the hiring of foreign workers,” he said.

Household incomes and living standards

Over-consumption is back after the 2014–2016 recession. The growth rates of real wages and real disposable incomes of households outstrip the growth rates of GDP and labor productivity. In 2017–2019, real wages rose by 29.8% and real disposable incomes went up by 17.5%, while GDP only grew by 6.9% and labor productivity by 8.8%.

However, the data on the growth rate of wages and household incomes are overstated, because the index of consumer prices regulated by the state does not fully reflect inflation. There are two alternative indicators of inflation: the consumer price index (CPI) and the GDP deflator index. The CPI overstates the inflation rate a little, while the GDP deflator index understates it.

It is vice versa in Belarus. The GDP deflator index increased 20% in 2017-2019, while the CPI went up 15.6%. Over the past three years, the CPI growth rate was below the growth rate of price indices in industry, construction, transport and other most important sectors of the economy, i.e. the impulses of price growth in these sectors did not reach the consumer market. When real GDP is calculated, sectoral indices and CPI are used, whereas only an understated CPI is used to calculate real wages and household incomes, which means that the growth rates of wages and incomes are overstated. On the plus side, the imbalance between the growth rate of wages and labor productivity is not as large as statistics show.

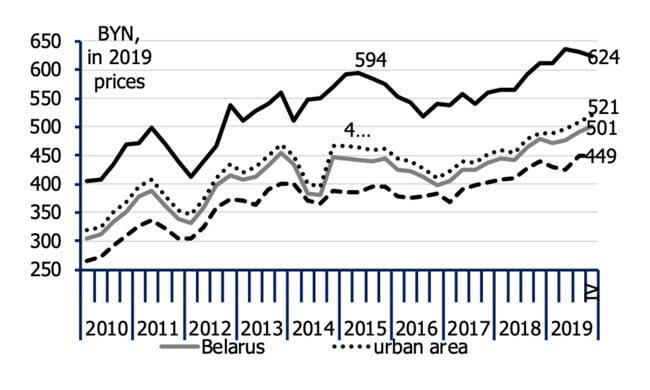

The living standards and the purchasing power of the population are more accurately characterized by average median incomes. In 2019, the average resident of Belarus (including children) had an income of BYN 501 per month, or BYN 17 per day (USD 8) (Figure 3). Given that the prices of many consumer goods in Belarus are comparable with prices in Poland, Lithuania and other EU countries, we can speak about a relatively low level of purchasing power. Every tenth family with two children (9.8%) and every fourth family with three children (24.3%) has an average disposable income per capita below the subsistence wage, even if state support was provided (the calculated subsistence wage stood at BYN 235).

Most workers have not noticed the 30% increase in real wages over the past three years. Material deprivation of households even increased 2019 to compare with 2016. Material deprivation refers to the inability for individuals or households to afford those consumption goods and activities that are typical in a society at a given point in time. There is not enough money to buy meat and fish, winter clothing, footwear, a washing machine, furniture, medicines, fuel for heating homes, fruits and toys for children, to pay utility and telecom bills, and cover unforeseen expenses in the amount of BYN 100.

In 2019, 51% of Belarusian households experienced at least one material deprivation (43% in 2016); 3.7% experienced four or more deprivations (2.1% in 2016); 27% of families could not afford to put aside even BYN 100 for rainy day (28% in 2018); 39% could not replace worn-out furniture in their homes (26% in 2018); 6-8% were not able to regularly buy fruits and children’s toys (6-7% in 2018).

Unemployment

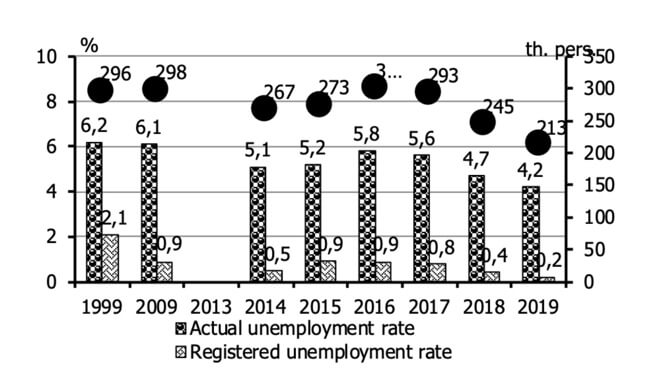

The unemployment rate fell in 2019 to 4.2%, the lowest average of recent years. The registered unemployment rate dropped to 0.2%, which is also the lowest point (Figure 4).

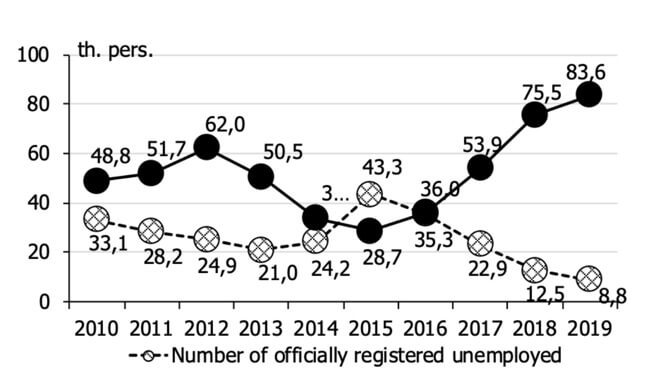

The number of the officially registered unemployed has been declining for four years in a row to the all-time low of 8,800 as of the end of 2019 (Figure 5). The number of job openings thus increased to 83,600 (21 per employee). The number of persons who apply for assistance to the employment and social protection authorities has decreased significantly from 240,000 on average in 2013–2017, to 200,000 in 2018 and 180,000 in 2019.

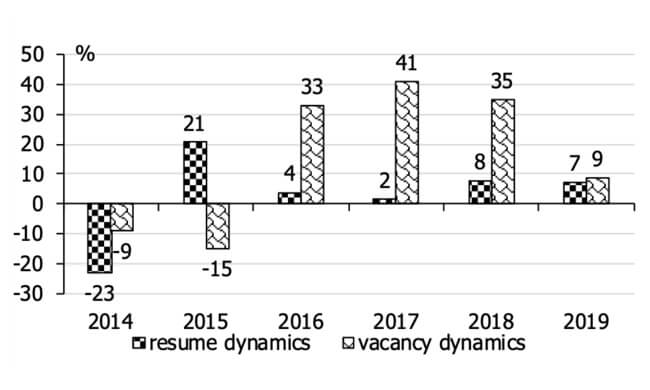

At the same time, the most popular rabota.tut.by job vacancy website shows the opposite dynamics. In 2018, the number of resumes posted there increased by 13,200 (8%) against 12,400 (7%) in 2019 (Figure 6).

As many as 180,000 resumes were posted on rabota.tut.by in 2019. The resume/vacancy ratio increased to 7.1 (7.8 in the first quarter of 2020, 6.4 in 2018). The number of resumes posted on similar sites (praca.by, belmeta.com, vakantno.by, jobs.dev.by, gorodrabot.by, joblab.by, trud.com, etc.) also increased in the past two years.

Judging by the ratio of registered and actual unemployment, the proportion of those who addressed employment agencies made up 4% in 2019 (15% in 2015–2016) or, perhaps, even less. Similar ratios of registered and actual unemployment are observed in some regions of Russia, which have data of opinion polls in addition to official statistics. For instance, in 2017, the unemployment rate in the Belgorod Region of Russia was at 3.8% according to the ILO methodology, the rate of registered unemployment being 0.68%, and the percentage of people applying to employment agencies according to an opinion poll was at 0.7%.6

This by no means indicates the uselessness of state employment services or their ineffectiveness. “The number of applicants does not largely depend on the agencies’ efforts,” says Vladimir Gimpelson, Director of the Center for Labor Market Studies at the Higher School of Economics.7 Among other things, it depends on the size of the unemployment benefit, which is set by the government, rather than the agencies.

It is worth noting that state employment agencies mostly offer low-paid jobs at state-run enterprises (65%) with wages at or below BYN 500, whereas rabota.tut.by assists white-collar workers and specialists with higher salaries in private companies. Usually, people try to find jobs on their own through acquaintances and ads, and by posting resumes on social media and on sites like rabota.tut.by, and only contact an employment agency if all previous attempts have failed.

The Ministry of Labor certainly understands that the algorithms of communication with those who seek employment agencies’ assistance should be reconsidered in order to increase their efficiency.8 2019 saw an innovation–electronic job fairs organized jointly with the Swedish Public Employment Service. The fairs are held several times a year for 3-5 days on e-vacancy.by.

Conclusion

The shortage of personnel in the labor market and the imbalance between workforce supply and demand will decrease in the coming years because of a decrease in labor demand and an increase in unemployment under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic in Belarus and the countries that are its main trading partners. The disproportion between wage growth rates and labor productivity in relation to GDP is expected to decrease for the same reason.

It was planned that Belarusian nationals, who are not registered as being employed, would pay the full price of natural gas and heat to be supplied to households from May 1, 2020. If the government will not postpone or cancel this, an increase in social tension and local protests is quite possible.

The labor market is likely to see a further contraction in the next two years. The twenty-year demographic transition in Belarus will not end before the mid-2020s. Until then, the ageing of the population will continue at the same pace as in the previous 15 years, and then this pace will slow down a bit.

The outflow of the working-age population will increase. The Belarusian economy is less prepared to deal with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic than the countries that provide jobs to Belarusians (Russia, Lithuania, Poland, etc.). As a result, the wage gap will get wider.

The number of foreign labor migrants in Belarus will not change significantly and will not be able to compensate for the outflow of workforce from the country. The migration policy is based on security, rather than economic interests. The Interior Ministry dominates over the Labor Ministry and other agencies in this respect. It will take years for economists to prevail when it comes to migration policies, and a paradigm change to take place.