Labor Market: Non-market status remains

Vladimir Akulich

Summary

In 2018, the Belarusian government continued applying administrative methods in an attempt to control the labor market, particularly to regulate wages, employment, birth rate and migration, although such efforts have already proved to be ineffective.

The annual average monthly wage did not reach the target of BYN 1,000. The proportion of the employed in the working-age population did not increase; the number of Belarusian labor emigrants continued to grow, and the birth rate was in decline. Administrative barriers diminished labor market flexibility, slowed down inter-sectoral and regional migration, and, therefore, complicated the transition to a post-industrial development stage.

Trends:

- Slowdown in workforce migration from the manufacturing industry to the high-tech services sector due to conservation of the obsolete structure of the economy and barriers to labor market mobility;

- Ineffective methods used to boost employment through a higher birth rate and forcing the unemployed to work;

- Administrative wage increases unsecured by labor productivity in GDP terms, which leads to accumulated imbalances and disproportions in the economy;

- Decrease in the unemployment rate to the natural level (4–6%), which by no means suggests that unemployment problems have been resolved.

Human resources

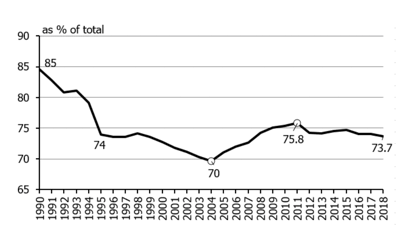

New decrees designed to stimulate employment were not much helpful: in 2016–2018, the proportion of the employed in the working-age population remained virtually unchanged and even slightly decreased (Figure 1).

The raised retirement age slowed down yet did not stop the decline in the number of working-age persons (a decrease by 472,000 people or 8% since 2006). This happens for two main reasons: the aging of the population and workforce migration. The authorities only count the number of registered migrants. In fact, several times more of them leave the country every year for work or permanent residence. According to Eurostat, Belarusians who move to Poland alone in one year could populate a large town (for example, in 2017, 42,700 people received residence permits and 35,000 obtained employment visas).

The aging of the workforce is also continuing, which is a common trend in Europe. As of early 2018, the average age of employable women was 42.8 years and the average age of employable men was 37.5 years, which in both cases is six months higher than five years back.

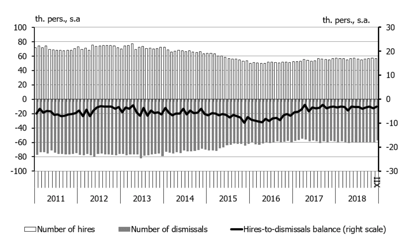

Over the past eight years, taking into account seasonality, there was not a single month when the number of hired workers exceeded the number of laid-off workers (Figure 2). As a result, the number of the employed decreased by 330,000 people (7%).

Note: s. a. stands for ‘seasonally adjusted’

In recent years, the outflow of secondary school graduates, who are leaving the country to study in neighboring states, has increased significantly. Poland, Russia and some other countries set not very demanding enrolment requirements for Belarusian nationals, including in economic and law colleges, whereas Belarus limits this admission. Belarusian universities reduce education services, and, accordingly, the number of the employed.

If the problems with creating high-paying jobs in the high-tech services sector did not concur with the population aging peak, the country would face serious unemployment problems. They are still there, though. The number of the unemployed is rapidly increasing, but this time in the form of well-deserved retirement with pensions paid from the state budget.

Besides, there is still an impressive outflow of labor force from Belarus. The growing deficit of the Social Protection Fund questions the state’s ability to fulfill its social obligations (even to pay pensions, not to mention normal unemployment benefits, or child and disability allowances).

In 2018, the birth rate decreased despite the regular official proclamations that large families should become a social norm. New measures to support families with children were announced, but the authorities keep ignoring the fact that the high birth rate over the past decade increased the burden on the social protection system just like the aging of the population.

Back in the 1960s, Nobel Prize winner in economics, Belarusian native Simon Kuznets said that present-day economic growth can lead to significant structural shifts in the economy and the social composition of society, as well as drastic changes in living and working conditions and lower birth rates. The degree of urbanization in Belarus (78.1% as of early 2018) is comparable with that in Switzerland and other developed economies. Therefore, the government should think not only about how to replace the retiring workers with the same number of young employees, but also how to increase the human capital and productivity of workers of the coming generations.

Based on econometric models, it has been proven that in conditions of economic stagnation and lumping poverty, an increase in the birth rate leads to an even greater slowdown in economic growth rates. A hundred years ago, Belarusian economic historian Mitrofan Dovnar-Zapolsky wrote that “when working to improve the economic structure, the population can at the same time restrain the birth rate in order to maintain the well-being of the current generations.”

Efficiency of the use of human resources

In addition to invested capital and labor, and scientific and technical progress, the efficiency of capital and labor utilization (capital and labor productivity) is an important factor of economic growth.

The number of jobs in Belarus is decreasing due to stagnation in some industries and automation in other ones. It would be logical to expect that workers would migrate from industrial enterprises to the high-tech services segment, but this does not always happen.

Workforce mobility in the labor market is extremely low, and it will hardly increase without stimulation. The shortage of new high-paying jobs largely stems from this issue. The manufacturing industry cannot provide high-paying jobs any longer, while the services industry cannot do it yet.

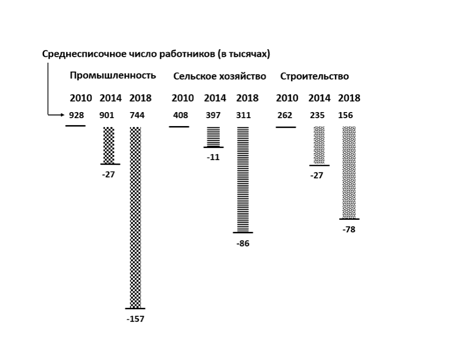

In the current decade, industry, agriculture and construction lost every fourth employee, 387,000 workers in absolute terms (Figure 3)

Industry Agriculture Construction

In 2010–2018, the number of people employed in production of machinery and equipment decreased by 40%, production of vehicles by 35%, and production of plastics by 32%. Moreover, output in these branches also fell by 30%, 35% and 18%, respectively. As a result, output per worker almost did not change. For example, it increased 0.3% on average in production of vehicles over the year.

The number of workers decreased significantly in the woodworking, metallurgical, electronics and textile industries. In 2010–2018, the number of employees dropped 30% in the woodworking industry and 28% in the electronics industry, but output either increased (woodworking, electronics), or changed very little (metallurgy, textiles). In comparable prices, output was up 45% in the woodworking industry and 33% in the electronics industry. Output per worker increased noticeably (by 110% in woodworking and 85% in the electronics industry). In this case, modernization and the scientific and technical progress have led to a decrease in the number of the employed without output loss. Disregarding this trend, educational institutions continue to train specialists for these industries. As a result, the largest proportion (29.3%) of the unemployed is constituted by those having degrees in processes and technology.

According to recent research (for example, the dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) modeling by the National Bank of Belarus),1 the scientific and technical progress influences the decline in employment in certain industries, yet generally leads to economic growth. This happens through a transfer channel in the form of a reduction in labor costs, a subsequent reduction in production costs and, accordingly, product pricing, the release of additional consumer demand, and increased output in some industries, which is accompanied by a higher employment rate. However, the scientific and technical progress involves retraining or acquisition of new professional skills and competencies by many workers.

It is advisable to foster labor mobility in the labor market, i.e. to raise unemployment benefits at least to the level of the minimum subsistence budget, and to abolish enslaving decree No.1 on promoting employment. It is important to strengthen the targeting of the social protection system, since not all currently employed persons will be able to adapt to new labor market requirements.

According to the forecast based on the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model, the number of the employed will continue to decline in agriculture, construction, and the manufacturing industry regardless of generated GDP. Employment in the manufacturing industry is already low (19.8% of total employment in 2018). It is desirable that the labor force switches to high-tech services, which is not happening yet.2 In recent years, the number of employees has slightly increased in trade, the IT sector, production of pharmaceuticals and healthcare, and it is decreasing in science and technology, education and public administration.

Household incomes and living standards

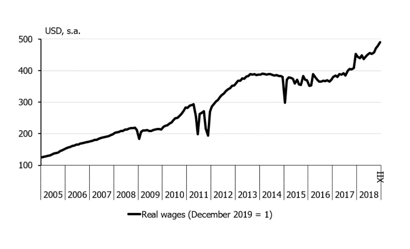

The workforce outflow problem can be solved by raising household incomes (backed by higher labor productivity) to a level comparable with incomes in the neighboring countries. Without structural reforms similar to those undertaken in Central and Eastern Europe and the Baltic States, this problem has no solution. In the recent history of Belarus, the average monthly wage in USD equivalent adjusted for seasonality and changes in the dollar’s domestic purchasing power, has never been over USD 500 (Figure 4).

Note: s. a. stands for ‘seasonally adjusted’

The purchasing power of USD in December 2019 = 1

Real wages (December 2019 = 1)

For comparison, in 2018, the average monthly wage in USD equivalent stood at USD 1,050 in Lithuania and USD 1,250 in Poland. According to Google Trends, Belarusians were most active in looking for jobs in Poland, rather than in Russia.

In 2017, for the third time in the economic history of Belarus, the president set the task to raise the average monthly wage to BYN 1,000 (USD 500 at the nominal exchange rate). On average, it reached BYN 815 (USD 420) in 2017 and BYN 958 (USD 470) in 2018. Although the task was not fulfilled (its fulfillment could lead to imbalances in the economy), even these figures turned out to be overstated.

For the second year in a row, household income growth rates have been outstripping GDP growth rates 2- or 3-fold. In 2018, real disposable household incomes increased by 8.4% year-on-year, real wages by 11.6% and real pensions by 14.6%, while labor productivity increased 3.6%.

The differentiation of incomes and the social stratification increase. Incomes of the rich grow faster than those of the poor. This stratification is observed in relation to the regions as opposed to the capital, the high-tech service sector as opposed to the public sector, ordinary families as opposed to large families, working persons as opposed to retirees, etc.

The social protection system in Belarus is categorical and therefore unfair. Quite often, welfare assistance is rendered to those who do not particularly need it, and is provided insufficiently to those who really do. The number of persons who could not afford a minimum basket of goods and services went up in 2015–2017. In 2018, 25% of families of four (30% in rural areas) had average monthly disposable incomes at or below the minimum subsistence budget per family member.

According to a household survey, 28% of Belarusian families cannot even save BYN 100 for a rainy day, 26% cannot replace decayed furniture in their homes, and 6% to 7% cannot afford prescribed medicines or regularly buy fruits for children.

Judging by statistical data on material deprivations, the population of the Brest region is the poorest. Even with financial aid from the state, 27% of large families were low-income last year. Every tenth child lives below the national poverty line.

More objectively, the population’s living standard is described by the average median wage, rather than the arithmetic average. In May 2018, the living standard was 25% below the arithmetic average. Three out of four workers have a monthly average wage below BYN 1,000 (USD 500). Taking into account expenses for the care of children, the median average monthly income per capita in the period under review amounted to BYN 430 (USD 210 per month or USD 7 per diem), and average food and clothing prices in Belarus almost do not differ from these prices in Poland and Lithuania.

Unemployment

In 2018, the labor market continued to recover from the 2014–2016 recession. The unemployment rate decreased considerably. In 2018, the number of the actually unemployed reached 245,000 people (4.8% of the total work force) against 293,000 (5.6%) a year before.

Belarus stands out for its huge gap between officially registered (0.3%) and actual (4.8%) unemployment. The number of actually unemployed is 13 times higher than the official number. This is due to the lack of unemployment insurance (except for a symbolic monthly benefit that averages 13% of the minimum subsistence budget).

There is quasi unemployment in Belarus: state-owned enterprises can keep workers on enforced leave for a long time. Also, the number of labor emigrants increased in 2018.

In recent years, Belarus has been among the top 10 countries in terms of the suicide rate. Quite often, suicides are caused by the lack of jobs and means of sustenance. Sociologists and human rights activists predict an increased number of suicides in 2019, because many unemployed people will not be able to pay full-price utility bills and late payment penalties (109% per annum).

The local labor market is quite strongly protected from the foreign labor force. The intensive aging of the population continues, i.e. the number of retirees exceeds the number of newcomers to the market. Besides, there is a significant differentiation in the level of unemployment, depending on the region, type of locality, age and profession. Therefore, a decline in unemployment does not mean that unemployment problems have been resolved.

Conclusion

Few believed that the two new decrees aimed at promoting employment would help, and they predictably did not. The proportion of the employable population even slightly decreased over the past three years. Enforcement of notorious decree No.1 in 2019 will most likely lead to a surge in social protests, suicides and emigration, rather than a higher employment rate.

The actual unemployment rate will remain the same due to the aging of the population and rampant labor migration outside the country, rather than rapid development of the economy. New measures to encourage having many children will not raise the birth rate. There will not be enough funds in the national budget for more generous measures, while smaller steps will not be appreciated by the population.

The Belarusian economic model with its predominantly administrative and mandatory distribution of funds is not capable of ensuring a high standard of living for a significant part of households. Labor productivity in Belarus is almost the lowest in Europe, which, in case of balanced development of the economy, can ensure USD 300–400 in the average monthly wage. Higher average wages in the last two years were achieved mainly by means of administrative interventions in the functioning of the labor market.

In the coming years, the Belarusian economy will continue to stagnate. Further administrative pay rises will lead into the trap of average income and increasing imbalances, which will entail macroeconomic adjustments through depreciation of the national currency.

A decrease in the number of jobs is caused by stagnation in some industrial sectors, or ongoing modernization in the others. The transition to Industry 4.0 is gradually beginning to manifest itself in Belarus, changing the sectoral composition of the workforce. According to the forecast model, the number of people employed in industrial sectors will continue to decline. For many this means the need to learn new trades. Employment offices and educational institutions should be prepared for these new challenges.