Labor Market: In the grip of excessive administrative regulation

Vladimir Akulich

Summary

In 2017, the number of the employed continued to decline. Demand for human resources increased. So did the competition for well paid jobs. In many districts, actual unemployment exceeds the natural rate. Compulsory wage rises continues to drive Belarus into an ‘average income trap.’ The trend towards an income gap increase remains.

Trends:

- The number of people employed in the economy is decreasing as a result of demographic aging and the workforce outflow;

- The problem of unemployment remains acute, especially in the provinces, despite labor shedding; labor demand and the competition for vacant jobs is increasing;

- The country lacks an unemployment insurance system; the labor market is inflexible, efficiency of the use of human capital assets is impaired;

- Belarus finds itself in the average income trap, and needs to cut wages in order to restore the competitiveness of old industries;

- The household income gap is growing.

Human resources

The population in Belarus is rapidly aging. According to statistics, the most intensive of the eight types of aging (unrestrained aging) was typical of 40% of cities and 25% of districts. Another 48% of districts are affected by the second most intensive type of aging: intensified aging. The countryside has become demographically older than urban areas due to migration to cities in the 1950s-1970s. Today, cities are aging as well. Calculations based on the UN methodology show that by 2017, all cities and regions entered the stage of demographic aging.1

Aging is determined by two factors. First, Belarus is in the middle of a 20-year demographic transition: the generation of the 1990s (with a birth rate of 10 per 1,000 population) enters the labor market, and the larger generation of the 1950s (with a birth rate of 25 per 1,000 population) is retiring. This process peaks in 2013-2021. On average, the working-age population will decline by 45,000 people, down by 0.7% per year.

Second, based on data of population censuses, Eurostat and Rosstat, the outflow of workforce from Belarus exceeds the migration gain.2 This contradicts the data published by Belstat, which only reports registered migration (like it does with registered unemployment). Around 70,000 people leave the country every year. For example, in 2015, 82,000 people found jobs in the EU, and 17,700 moved to Russia for permanent residence alone. At the same time, 12,800 people moved to Belarus from Russia, which means that Russia lost 4,900 to Belarus. The amount of money transferred from abroad is growing every year. In 2017, Belarusians employed outside the country transferred USD 1.05 billion (0.86 billion in 2016), which is comparable with total exports of the IT sector (USD 0.96 billion in 2016).

Over the past decade, the working-age population decline was estimated at 466,000 people (8%). In conditions of a solidarity pension system, this leads to an increase in the demographic burden on the employed and a deficit of the Social Protection Fund. In recent years, it has been covered by subventions from the state budget.

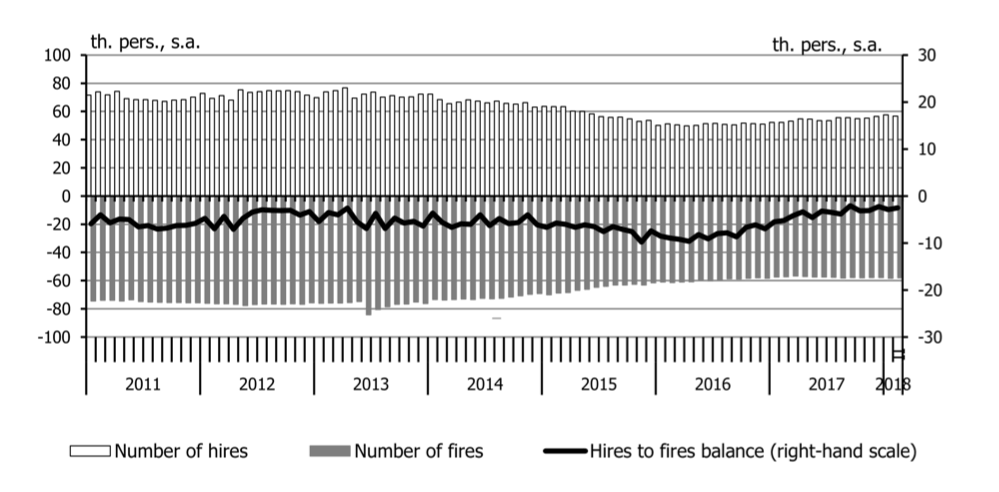

Over the past seven years, taking seasonality into account, there was not a single month when the number of hired employees did not exceed the number of fired employees (Figure 1).

The government sees stimulation of the birth rate as the best solution to the aging problem. A wrong moment was chosen for that, though. The increase in the birth rate has led to a reduction in the employed working-age population (by 200,000 over the past 10 years) and increased expenditures of the Social Protection Fund. Besides, today’s children will not enter the labor market before the 2030s.

The government finally announced a retirement age increase (step by step until 2022). However, experts say this will not be enough.

In order to involve working-age persons in the economy as much as possible, the president issued decree No.1, which replaced decree No.3 on ‘social parasitism.’ In 2017, the proportion of employed persons of working age made up 74%. The reserve for its increase is insignificant. In 1995-2017, this proportion was at 73%, and only reached 82% in 1990-1994. A Belstat’s household survey shows that in 2012-2017, on average, 30,000 persons did not have the need or desire to work, and another 35,000 gave up looking for jobs believing that it was impossible to find one. Engagement of these individuals as workforce would increase the proportion of the employed to 76%. The rest are temporarily jobless for valid reasons (studies, care for children or the elderly, service of prison terms, treatment for disability), or are looking for jobs, or are employed outside the country.

In developed economies, the population aging problem is being solved by employing migrants.

Efficiency of the use of human resources

The problem of the workforce outflow from the country can be solved by increasing household incomes (supported by labor productivity growth) at least to the amounts paid in the neighboring countries. Without structural reforms similar to those carried out by the CEE and Baltic States, this problem has no solution. In the past decade, the aggregate factor productivity, which includes labor productivity, has been steadily declining. According to IMF calculations, for example, one worker in the Czech Republic generates the same GDP as two workers in Belarus, the main reasons being the high materials consumption, redundant employment in state-run enterprises, inflexible labor market due to the absence of unemployment insurance, and the top-down management style with a fettering contract system, which does not provide employees opportunities for professional development and self-realisation, resulting in poor performance and low wages.

New technologies are needed to reduce the materials consumption and, consequently, production costs. They can come with investments from the more developed markets. For example, in early 2016, the president demanded that state-owned enterprises reduce production costs by 25%. In 2015, it consisted of the costs of materials (64%), wages (18%) and deductions to the Social Protection Fund (6%). This means that production costs can only be reduced by decreasing these components. Each percent of a reduction in materials costs requires considerable investment and time. For example, in 2010-2014, when the proportion of investments in GDP was still high and various modernization programs were in progress, the materials costs only decreased by 3%.

Post-crisis recovery

The labor market returned to the pre-crisis level with respect to a number of indicators. Demand for labor continued to rise for the second consecutive year. The number of job openings in employment agencies’ databases increased from 29,000 as of late 2015 to 36,000 in late 2016 and to 54,000 as of the end of 2017 (only 2012 saw more). As many as 242,000 people applied for assistance in finding jobs in 2017 (239,000 in 2016 and 250,000 in 2015). RABOTA.TUT.BY Center analyzed its own vacancy database and reported that in 2017, the number of openings continued to increase (by 40% in 2017 and 33% in 2016).3 According to IMF calculations, quasi unemployment in 2017 fell to 0.7% (2.3% in 2016 and 3.1% in 2015).

The official number of vacancies in 2017 was 150% higher than the number of people applying to employment agencies. RABOTA.TUT.BY says there were eight job seekers per opening, same as in 2014. The latest data reflect the real competition in the labor market to a greater extent and explain why 40% of applicants could not find jobs in 2017 for over six months. The average duration of unemployment among those looking for jobs through employment agencies was 4.2 months in 2017 (4 months in 2016), whereas those who were looking for jobs on their own stayed jobless for 6.5 months (7 months in 2016). This shows that the time limit set for job search by Decree No.1 (three months) is unreasonably understated.

Unemployment

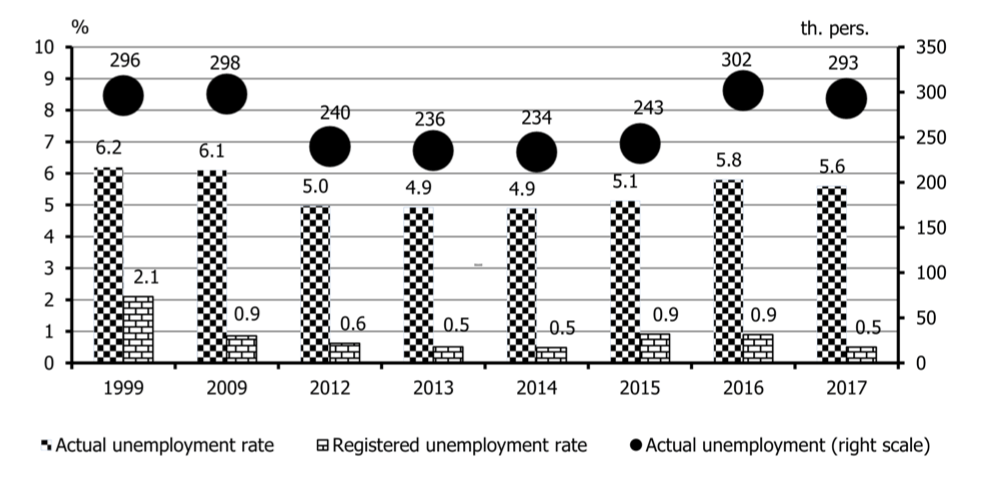

In 2017, the country totaled 293,000 unemployed persons, or 5.6% of the able-bodied population (Fig.2).

In Belarus, state-owned enterprises may refrain from staff cuts and keep employees on forced leave for a long time. Given this quasi unemployment, the actual unemployment rate in 2017 was at 6.3% (8.1% in 2016 and 8.2% in 2015).

There is a significant differentiation in terms of unemployment in the provinces. In the Molodechno district (based on the results of the pilot population census), actual unemployment in 2017 made up 9.1%. In many districts, unemployment exceeds the natural level by 5% to 6%.

As of the end of 2017, Belarus numbered 23,000 registered unemployed persons, 0.5% (there were fewer only at the end of 2013). This constitutes 8% of the total number of the unemployed. The low unemployment benefit (13% of the subsistence wage, or 3% of the average wage), imposed community service and the shortage of high skill jobs in the vacancy database make little sense of the official registration as unemployed. People usually look for jobs without seeking help from the state.

‘Average income trap’ and the growing income gap

Belarus is generally thought to be an average income country. This is true in terms of PPP-based GDP per capita. In nominal terms, GDP per capita in Belarus is almost two times lower than the world average: USD 5,100 in 2016 and USD 10,000 thousand, respectively, according to the IMF. The real purchasing power of the population is reflected by nominal GDP in the open global world, rather than GDP (PPP). For example, with these incomes one can hardly buy high-quality imported goods. In 2017, Belarus was last but one in Europe with respect to the number of purchased new cars (4 per 1,000 population). For comparison, 19 new cars were purchased in Estonia, 26 in the Czech Republic, and 42 in Germany.

Income differences are increasing. The gap between the arithmetical average and median average wages has grown by 50% in four years (21% in November 2013, 24% in November 2014, 28% in November 2015, 30% in November 2016, and 32% in November 2017).4 The average wage is getting further and further from reality. In November 2017, in half of the districts, over 50% of employees were paid less than BYN 500.

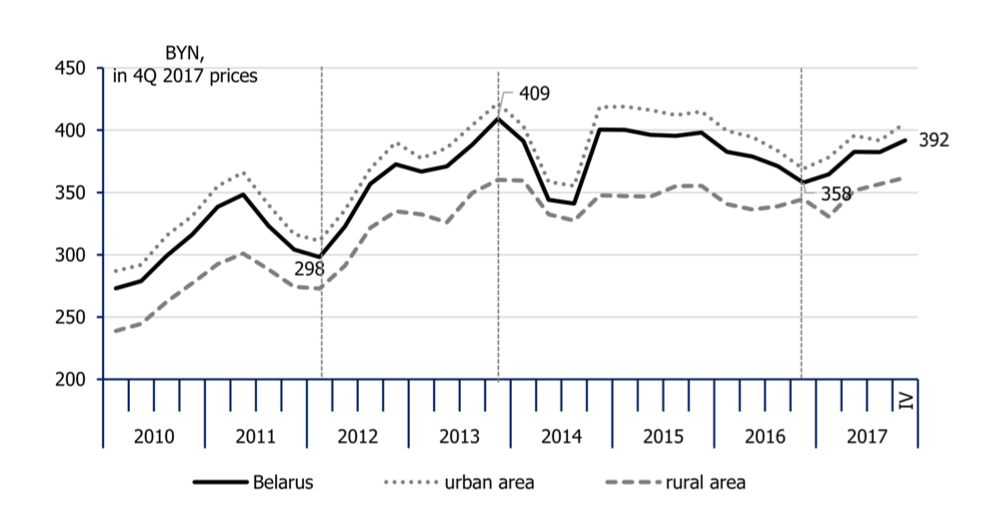

The monthly median disposable income per capita in the fourth quarter of 2017 was BYN 392 (USD 6 per diem). In the past five years, this amount has changed little ranging BYN 350 to 400 (Fig.3). The social protection system is not targeted (only 2% of the funds are distributed by individual requests). In 4Q17, 30% of large families had incomes below the poverty threshold.

In 2017, the task was set again to achieve the average wage of BYN 1,000 or BYN 500 at a nominal rate. The annual average wage was raised to BYN 815, although this figure looks overstated. The wage growth rate outstripped the labor productivity growth rate (6.2% and 3.6%, respectively).

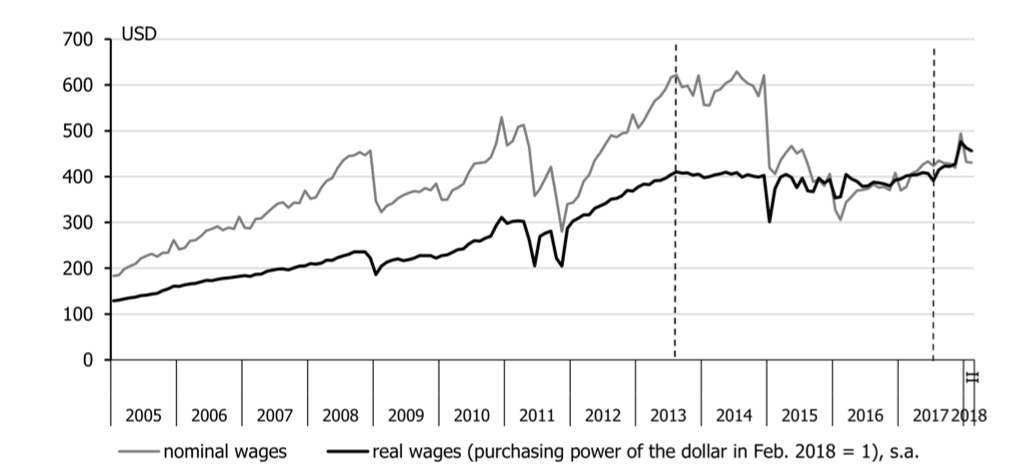

Compulsory wage rises undermine the price competitiveness of domestic producers. Even without this, we can say that Belarus (like Russia) was caught in an ‘average income trap’ five years back. Since mid-2012, three years before energy prices were lowered, the growth rates of the economies of Belarus and Russia have almost zeroed. Wages in Belarus in 2012 and the first half of 2013 rose for the first time to USD 600 at par or USD 400 in today’s dollar prices (Fig.4). In 2012-2013, the average annual growth rate of wages was reported at 19% and GDP at 1.5%. Despite the depreciation of the Belarusian ruble in 2014-2016, the real wage in USD equivalent has since been maintained at USD 400. Furthermore, it reached the bar of USD 450 in the second half of 2017.

With the current labor costs, the costs of many domestic goods are higher than elsewhere in the world. Stuck in the average income trap, Belarus is losing the competition to countries where the cost of industrial goods is lower. Belarus cannot compete with developed economies, which possess skilled workforce, latest technologies and innovative capacities.

Manufacturers of sophisticated commodities are hit by increased labor costs the most. Wages are being inflated at all processing stages. Besides, import substitution was ordered from above. All this affects prices of finished goods. For example, Belarusian machine tools cost twice as much as German analogues. Producers of raw materials and resource-intensive goods suffer less from unjustified wage rises. As a result, the proportion of medium- and low-tech goods in exports has decreased from 58% in 2008 to 40% in 2016. They are being replaced by raw materials and less resource-intensive goods, the proportion of which increased from 24% to 42%. The share of high-tech goods remained at 1.5%.5

There are two ways out of this situation. The first one is to lower the average salary to USD 300-350 to regain competitiveness in export-oriented industries. The population will be poorer, of course. The second way is to bring about reforms, join the global value chains, choose particular lines of production to focus on, foster foreign investment and acquire high technologies that can reduce material consumption and make goods competitive with USD 500, 700 and even 1,000 in wages. For example, the average wage in Lithuania amounted to USD 1,000 in 2017, and the country fosters production of goods intended for exports to the EU.

Conclusion

Belarus’ workforce is shrinking due to the natural aging of the population and the outflow of young people from the country. This decline will continue, as the measures taken are not enough. Decree No.1 will not change the situation, since jobs are created by investors, not by government officials. The cost of its administration will exceed the possible benefits. The employment decline will lead to a growing deficit of the Social Protection Fund and slower economic growth.

In many districts, actual unemployment exceeds the natural rate. The income gap is growing. The average wage grows mainly in big cities.

Belarus’ economy has got into the ‘average income trap.’ Due to compulsory wage rises, the country loses its position in the old mid-tech industries thus being unable to master high-tech ones. Without structural reforms, a macro adjustment is required to regain competitiveness. Subsequently, wages will return to a level that ensures competitiveness of products in export-oriented industries. In the current technological modes, this level is very low.