Labor market: Trapped in low-paid employment, unemployment and poverty

Vladimir Akulich

Summary

Belarus is in a state of demographic transition. The number of the employed is decreasing. This mitigates the problem of unemployment, but increases the demographic burden on the employed and makes it harder for the government to fulfill social obligations. So far, this issue has been tackled through an increase in the degree of centralization of finance.

The labor market has adjusted to the recession largely through lowering wages and, to a lesser extent, higher unemployment. Low-paid employment and the lack of jobs have resulted in the growth of poverty.

Trends:

- The number of working age population and the number of the employed are falling despite an increase in the number of working pensioners;

- The demographic burden on the employed is increasing, and so is the birth rate; the government encourages families to have many children;

- Real household incomes are shrinking, and the actual unemployment rate is going up due to the economic recession;

- The demand for labor is increasing that may indicate a gradual economic recovery.

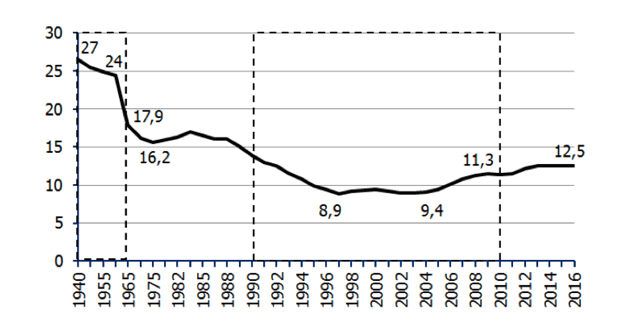

Demographics

Belarus is in the middle of a 20-year demographic transition. In 2006–2023, workers born between 1945 and 1965 are not of employable age any more, and workers born between 1990 and 2010 are entering it. In 1945–1965, the crude birth rate averaged 25 per thousand. In 1990–2010, it was 10 per thousand, which is 150% lower (Figure 1).

As a result of the demographic transition, the working age population has decreased by 475,000 or 7.0% over the past decade. In the next seven years, the decline will continue at about the same pace, and then the rate of decline will slow down (Figure 2).

From 2023, the women born after 1965, when the crude birth rate dropped to 18 per 1,000, will be beyond employable age. The increase in the retirement age, which started in 2017 and will end in 2022, will have its effect.

Employment

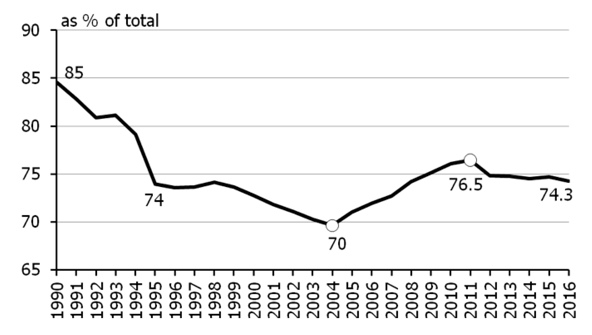

Although the demographic transition and decline in the working age population have been observed since 2006, the number of employed persons increased in 2006–2010 and only began to decrease in 2011 (Figure 3).

The increase resulted from the growth in the proportion of the employed at active working age from 70.0% in 2004 to 72.0% in 2006 and 76.5% in 2011 (Figure 4). That is why the employed population continued to increase from 4,470,000 in 2006 to 4,703,000 even though the working age population was in decline in 2010 (see Figure 3).

In 2011–2016, the proportion of the employed in the working age population remained approximately the same, constituting around 75.0% (Figure 4). Accordingly, the proportion of the unemployed made up 25.0%. Therefore, the employment decline was mainly due to a decrease in the working age population (by 380,000, or 7.0%). At the same time, the number of the employed decreased by 289,000. Employment would fall even more, if not for working pensioners, whose number increased from 270,000 in 2006 to 340,000 in 2011 and 430,000 in 2015.

In the composition of the unemployed working age population in 2011-2015, only two segments underwent significant changes. The number of students decreased by 112,000 (8.0%) and the number of parents on parental leave increased by 87,000 (6.0%) (Figure 5).

In 2012, the National Statistics Committee of Belarus (Belstat) started a household survey to conduct employment research. This made it possible to find out what 455,000 persons were engaged in, not being listed among workers or students in 2011, and whom the prime minister proposed to involve in financing of social spending for the first time in August 2012. After the survey, the number of the unaccounted unemployed decreased four-fold to 111,000 in 2012.1 The same number was reported in 2015 (see Figure 5).

It was found out that in 2012-2016, on average, 211,000 persons did not have a job, were not registered by employment agencies, but were actively looking for a job and were ready to start working anytime. As defined by the International Labor Organization, such persons are classified as unemployed. There is also a category of people who have been looking for a job for a long time, but in vain, lost hope and stopped looking. In 2012-2015, there were 35,000 such persons on average. As defined by the ILO, they are not considered unemployed, but they do not have jobs either.

According to the household survey, in 2012–2015, an average of 55,000 Belarusians legally worked outside the country (93% of them in Russia) and paid taxes there, and this correlates with the balance of payments. In 2016, Belarus received USD 417 million under the article “remuneration of labor from abroad”, which equals to 58,000 average annual wages in Russia.

In 2012–2015, an average of 125,000 people managed private households. According to Belstat’s new surveys, an average of 30,000 persons did not need or did not want to work in 2012–2015.

The unaccounted balance of 111,000 persons classified as “other unemployed persons of working age” in disaggregation by region suggests that the vast majority of them (90%) are individuals who work unofficially outside Belarus. In 2015, 84% of the “persons working abroad” accrued to four regions – Mogilev, Gomel, Vitebsk and Brest. In the category “other unemployed persons”, 90% accounted for the same four border regions. In other years, the coincidence in the breakdown in disaggregation by region for the two specified categories is even more pronounced: for example, 83% and 85% in 2012, respectively. It can be concluded that approximately 100,000 people worked outside Belarus unofficially.

The statement that a large proportion of the employed is engaged in off-the-books economic activity is a myth, which cannot be substantiated with documentary evidence. For example, in the central regions of Belarus (Minsk city and Minsk region), which are the place of residents of 38% of the working age population, only 5,800 persons, or 0.25% of the working age population, including those unofficially working abroad, are categorized as “other unemployed.”

It is not uncommon when a part of revenues goes off the books and officially registered employees are partly paid envelope wages. Such employees evade a part of taxes, but are considered employed and do not fall within the scope of decree No. 3 ‘On the Prevention of Social Parasitism.’ The number of persons working without official registration is around 10,000 or 20,000, or 0.25% of the working age population.

Belstat’s household surveys showed who those 455,000 unaccounted unemployed persons were in 2011. As it later turned out, half of them were unregistered unemployed (210,000), one-fourth were household managing individuals (130,000), another one-fourth were supposedly unofficially employed outside Belarus (100,000), and only one-fifteenth were persons, who did not need or did not want to work (30,000).

In Belarus, the proportion of individuals employed in production industries is decreasing (by 240,000 in 2011–2015), and the proportion of those employed in the service sector is going up (by 80,000). The total number of the employed decreased by 160,000. As many as 250,000 persons were already beyond employable age, and 90,000 persons of retirement age continued working. In 2011-2015, the number of labor migrants did not change considerably.

On the one hand, the demographic transition alleviates the problem of unemployment. On the other hand, the demographic burden on the employed working age population is growing. According to Belstat, in early 2016, there were 727 persons beyond the employable age per 1,000 persons of the working age population. Given that 25% of the working age population is unemployed and 16% of the population over working age is still employed, the real load on the employed is demonstrated by the modified demographic load factor. In 2016, there were 1,152 unemployed persons at employable and unemployable age per 1,000 employed (those of working age and working pensioners) (Figure 6).

The demographic burden also increases as a result of an increase in life expectancy and the number of persons beyond employable age. According to Belstat, in 2015, the life expectancy of men and women aged 65 was at 78 and 83, respectively. This refutes the argument of the opponents of the retirement age rise, who say that most men will not have time to enjoy retirement benefits even if they live to that age.

Instead of stimulating business activity amid the recession, the government chose to increase the tax burden in 2015–2016. In 2016, a reduction in GDP did not lead to a decrease in enlarged government budget revenues. The degree of centralization of finance (GDP quota) has been growing for the second year in a row and reached the record-breaking 42.7% of GDP in 2016. For comparison: it was at 41.3% in 2015, 40.3% in 2014, 40.8% in 2010–2013 on average, and dropped to a minimum of 39.2% in the crisis year of 2011.

The labor demand began to increase in 2016, which may indicate a gradual recovery of the labor market. The number of vacant positions offered by employment offices increased from 31,000 in 2015 to 32,000 in 2016 (4.0%). 239,000 persons (5.4% of the economically active population) were looking for jobs resorting to the services of employment offices last year (250,000 or 5.7% in 2015). RABOTA.TUT.BY research center analyzed its own database of vacancies and CVs and reported that in 2016, the number of job openings increased by 33%, while the number of job applications reduced by 4%.2

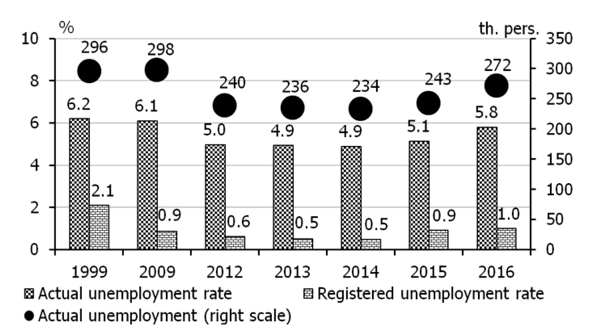

Unemployment

In 2016, the Belarusian economy continued to be in recession. There was a 2.6% GDP decline last year (3.8% in 2015). The unemployment rate went up from 4.9% in 2014 to 5.1% in 2015 and 5.8% in 2016. The registered unemployment rate also increased from 0.5% in 2014 to 1.0% in 2016. The number of the unemployed increased from 243,000 in 2015 to 272,000 in 2016, or by 12.0% (Figure 7). At the same time, the number of the registered unemployed reduced from 41,000 in 2015 to 39,000 in 2016 (a 5.0% decrease).

Belarus lacks a full-scale social protection system for the unemployed. Unemployment benefits in 2014–2016 made up 3% of the average wage, or 13% of the subsistence wage. For comparison, unemployment benefits in the European Union range between 50% and 70% of the average wage. The proportion of the unemployed in Belarus who received unemployment benefits in 2016 made up 14% (17% in 2015). The rest do not apply for official registration because the miserly unemployment benefits are not worth bothering with.

In 2016, the Social Protection Fund allocated BYN 26.8 million, or 0.03% of GDP to support the unemployed and promote employment. The amount planned for 2017 stands at 38 million, or 0.04% of GDP. In the OECD member states, average unemployment benefits constituted 0.9% of GDP in 2013.

The average period of unemployment increased from 4.1 months in 2015 to 4.2 months in 2016. The average period of finding a job also increased from 1.9 months in 2015 to 2.3 months in 2016. Decree No. 3 unreasonably understates the period of six months of unemployment, during which jobless persons must pay the tax on ‘social parasitism.’ According to Belstat, every fourth (24%) unemployed registered by an employment office in 2015 was not employed in six months. It takes seven months on average to find a job independently. Those looking for jobs with the help of employment offices spent five months on average to find one in January-September 2016. For comparison, it took 6.4 months in 2000 and 5.8 months in 2005. The average unemployment period in the CIS was 10 months in 2013, eight months in the OECD in 2015, 18 months in the EU in 2015, and 6.5 months in the G7 countries in 2015.

Real household incomes

The labor market adapted to the recession, mainly not through an increase in unemployment, but through a decrease in wages. In 2016, real household incomes dropped 7.3% (5.6% in 2015). The median level of average real disposable incomes per capita decreased by 4.4% (it was at 4.5% in 2015). According to Belstat, 38.0% of households reported a deterioration of their financial situation last year, and only 9.0% said it was improving (33.0% and 11.0% in 2015, respectively). At the same time, 31.0% of households estimate their financial situation below the average and only 3.0% said it was above the average (30.0% and 4.0% in 2015, respectively).

Low wages and their reduction push workers to look for new higher-paid jobs. According to Belstat, in 2012, job change was a way to increase incomes in 28.0% of households (second most popular option after off-hours jobs). In low-income households, job change as a means to increase incomes is the main option, making up 39.0%.

These figures correlate with the results of other studies. According to RABOTA.TUT.BY research conducted in 2016, 48% of respondents quit jobs due to low wages.3 When asked “What do you expect from the management in 2016?” a majority of employees (73%) said they were waiting for a wage raise.4 The implementation of decree No. 3 and the presidential directive to achieve USD 500 in the average wage by the end of 2017 can reduce the motivation of employees to look for new higher-paying jobs and lead to the lower mobility of the labor market.

The possibility to cut wages enables state-owned enterprises to maintain overemployment. If the government decided to raise wages using administrative methods, enterprises can start getting rid of excessive workforce that will lead to a jump in unemployment. According to IPM Research Center’s estimates, a 12.9% reduction in employment will be required to achieve an average wage increase from USD 400 in December 2016 to USD 500 in December 2017 provided that the exchange rate of the ruble will remain the same and the rates of inflation and GDP will remain as planned.5

Conclusion

In the near future, Belarus may face a number of challenges, especially a shortage of workforce needed to resume strong economic growth. As the ageing of the population continues, the demographic burden on the employed and businesses may be overwhelmingly heavy. The increasing birth rate and the national demographic policy that encourages having many children only increases this burden.

High taxes demotivate workers and have a negative effect on investment activity and competitiveness of commodities. Already now, there is a need to moderate regulations on labor migrants and build a system of selective involvement in the economy.

The increase in retirement age will slow down, but it will not stop the employed population decline. The situation will not be remedied by attempts to force certain categories of unemployed persons of working age to work or pay the tax on ‘parasites’ to finance government spending. There are dozens of truly unemployed persons, not hundreds of thousands. Therefore, after 2022, it would make sense to continue raising the retirement age to 65 years for men and women as the IMF suggests.

In order to prevent the growth of poverty, Belarus should follow the recommendations given by the World Bank and increase unemployment benefits to the level of the subsistence wage.

As concerns the income policy, it is advisable to abandon the voluntaristic idea to raise wages all at once. This will either lead to a deterioration of employment and rise in unemployment, or undermine the competitive capacity of producers.