Belarus and Russia: From brotherhood to alliance

Anatoly Pankovski

Summary

Moscow has almost given up the idea of imposing heavy demands on its main ally, being ready to invest in Belarus not requesting its unconditional support for the Kremlin’s confrontational actions in relation to Ukraine, Turkey and the West. Moreover, in these circumstances, it looks like the Kremlin sees some advantages in a greater involvement of Belarus in regional and international politics. In all other respects, the long established trends in Belarusian-Russian relations persisted in 2015: Belarus’ solid alliance with Russia with a certain freedom when it comes to the cooperation with third countries, active, although not very effective lobbying of Belarusian producers in the Russian market, the preserved special regime of supplies of energy resources to Belarus, and credit support when benefits of this regime fade out.

Trends:

- A growing gap between the real and the declarative dimensions of the integration;

- A considerable decline in the mutual trade turnover and a downfall of Belarusian exports;

- Deterioration of the composition of Belarusian exports;

- A reduction in Belarus’ benefits from the integration;

- New elements of advocacy of Russia’s foreign policy interests by Minsk.

Official plan: exceptional friendliness

The period under analysis was quite rich in contacts and interactions on a bilateral basis and within the post-Soviet unions that gave officials and observers a reason to speak about a stepping up and more profound integration. The most important high-level contacts are connected with the functioning of post-Soviet integration organizations: a session of the Supreme State Council of the Union State of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus (March 3); a meeting in Astana within the framework of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) (March 19–20); the celebration of the 18th anniversary of the Union State, etc. If we recognize the ‘deepening of the integration’ as a sufficiently adequate description, the following would be correct as well: integration instruments did not work smoothly and effectively, so a manual adjustment of the interaction was constantly required.

For the first time in the history of the bilateral relations, President Lukashenko’s official visit to Moscow after his re-election for a new term in office was not the first but third after the trips to Hanoi and Ashgabat. Vladimir Putin did not attach any importance to this interesting fact and, judging by his words of welcome, did not notice it at all. The meeting was extremely friendly. Both presidents expressed full understanding on the whole range of problems from the foreign policy to the economic integration.

However, this friendliness and mutual understanding was achieved by leaving all specifics aside. Nothing was said about either the matters that caused concern in Moscow (Ukraine, Turkey, Syria, or the Russian military airbase in Belarus), nor the issues of concern to Minsk (credit support, giving Belarusian commodities the national status on the Russian market, etc.). Considering the whole bunch of all unresolved issues, problems and half words accumulated by that time, it is fair to say that Minsk and Moscow have reached the ultimate stage of political hypocrisy in their bilateral relations.

Meanwhile, the gap between the declarative and the real dimensions of the Belarusian-Russian integration continued to widen last year. On the one hand, several encouraging initiatives were articulated and several announcements were made. In particular, at the session of the Supreme State Council of the Union State held March 3, Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke about a possibility of a common visa area within the Union State. In turn, Deputy Foreign Minister of Belarus Alexander Mikhnevich said it was premature.

At the meeting in Astana, Putin spoke about the possibility of a single currency union within the EEU. The Belarusian president did not second his Russian counterpart saying that the single currency launch was “not a question of the day.”1

On the other hand, five basic integration projects2 have not progressed whatsoever. As Russian Vice Premier Arkady Dvorkovich said, their implementation requires political will. Belarus and Russia, apparently, show none. Finally, as concerns Belarus, its first year as a EEU member brought not so much benefits – primary (trade) and secondary (energy rent and loans) – as expenses.

Unequal exchange

Belarusian-Russian trade turnover went down 26.3% against 2014 from USD 37.37 billion to 27.53 billion. Belarus’ exports to Russia dropped 31.6% to 10.38 billion dollars and imports were down 22.8% to 17.1 billion. The usual trade deficit decreased the least (6.8 billion). This is the worst turnover index since 2009. Compared with 2012, the best year in the history of Russian-Belarusian trade), the overall decline reaches 62.7% (Table 1).

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | % against 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trade turnover | 23,444 | 28,035 | 39,439 | 43,860 | 39,742 | 37,371 | 27,533 | 73.7 |

| Exports | 6,718 | 9,954 | 14,509 | 16,309 | 16,837 | 15,181 | 10,389 | 68.4 |

| Imports | 16,726 | 18,081 | 24,930 | 27,551 | 22,905 | 22,190 | 17,144 | 77.2 |

| Deficit | 10,008 | 8,127 | 10,421 | 11,242 | 6,068 | 7,009 | 6,755 | 96.4 |

It could be said in 2014 that the decline of Russian-Belarusian trade was in many respects caused by the devaluation of the Russian ruble. The decline in 2015 was largely due to the global oil price downturn. Given the direct correlation between trade trends and prices of raw commodities, Belarusian-Russian trade can be regarded as a particular case of the global trade recession (although this case is aggravated by some other impacts).

Centre for European Policy Studies Director Daniel Gros says commodity prices affect not only the value terms of trade, but also its volume, because higher oil and gas prices are forcing industrialized countries (consumers of raw commodities) to increase exports in order to cover the costs of the same volume of imports of raw materials.4 This seems to be true given that the proportion of Russia in Belarus’ total turnover remains consistently high at 48.0% (49.0% in 2014), while raw commodities – oil, gas, oil products, potash and timber – remain the main items in export-import operations of Belarus.

There is a clear disproportion in Belarusian-Russian trade. Russia mainly supplies raw commodities of critical importance to Belarus, while the latter mainly provides Russia with end products. In 2015, the prices of Russian oil, gas and electric energy were falling less rapidly than the prices of Belarusian engineering products and foods (Table 2). The export of foods to Russia rebounded in quantitative terms in mid-2015, but the trade return shrank almost one-third in money terms.

| By value | By quantity | |

|---|---|---|

| Trucks | 41.0 | 66.4 |

| Tractors | 62.2 | 47.8 |

| Agricultural machinery | 85.7 | 44.8 |

| Oil products | 50.1 | 35.0 |

| Furniture | 86.5 | 62.9 |

| Meat | 109.3 | 77.5 |

| Milk* | 117.0 | 75.0 |

| Cheese | 109.1 | 79.3 |

| Smoked fish | 166.0 | 92.7 |

*Rough estimate regarding dairy and semi-finished dairy products

This disproportion occurs mainly due to unequal terms of trade for Belarusian goods in the Russian market. Moreover, these terms are formalized in EEU regulations and institutional lobbying schemes of Russian companies.

In general, despite small local successes,5 the economic integration with Russia remains disadvantageous to Belarus. Therefore, over the first two months of 2015, equitable trade relations were on the agenda of numerous negotiations between the Belarusian and Russian leaders. At a meeting with Russian top officials during the Minsk session of the Supreme State Council of the Union State, Lukashenko pointed out that the mutual trade turnover had been dropping for three years. “That’s why the removal of barriers to ensure the effective functioning of the single market of goods, services and capital, and mutual support are our common area of interest,” he said.6

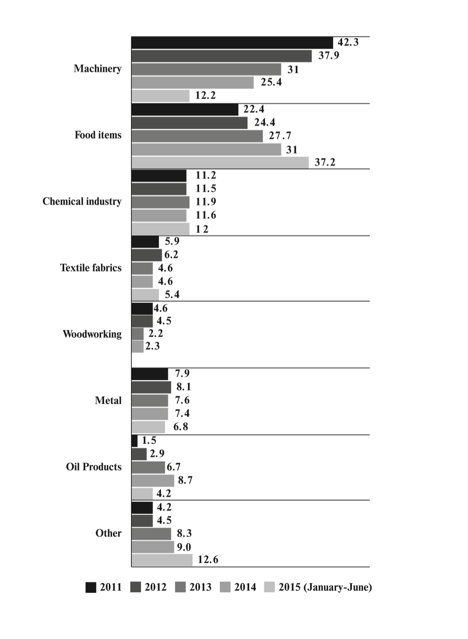

However, efforts made to advocate economic interests of Belarus in the EEU and the Union State remain ineffective. Probably, if it was not for Russia’s trade war with Ukraine, Turkey, the European Union and the West (the destruction of foods before TV cameras in August 2015), which gave Belarus a chance to partially recoup losses incurred from the EEU membership, Belarusian exports would dwindle even more. The composition of Belarusian exports looked at in a long retrospect makes its progressive degradation obvious: Belarus gradually turns from an ‘assembly shop’ into a sort of agrarian and raw material appendage of the Russian market (see Figure 1).

Secondary benefits

As before, Belarus purchased Russian oil and gas at the lowest prices in the region. However, the trend of the past two years continues: Belarus’ oil and gas rent is shrinking as the prices of energy resources go down,7 although not very rapidly. Its approximate total amount in monetary terms can be presented as follows: around USD 2.5 billion is a bonus from the difference between the purchasing and the global oil prices; 1 billion comes from custom duties on oil products, which Belarus keeps for itself; another 1.8 billion are annual ‘savings’ from the difference between the purchase and the average European price of gas.

So, in 2015, Belarus’ total energy rent amounted to USD 5.3 billion. This is not enough to fully compensate the trade deficit, which reaches 6.8 billion, but gives an idea of how much Russia could lend to Belarus in 2015: 1.5 billion.

In late April, Russia gave Belarus a government loan in the amount of RUB 6.2 billion (around USD 110 million) to recharge the gold and currency reserves. On July 24, the Russian government signed an agreement on a new ruble loan to Belarus in the amount equivalent to USD 760 million. The loan was granted for ten years to service and pay off previous Russian loans to Belarus allocated from the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development (EFSD). The money was transferred to the account of the Ministry of Finance of Belarus on July 28.

In 2015, Russia gave Belarus at least 600 million dollars less than the latter requested, Belarus predictably asked Russia for another loan, that time USD 3 billion, apparently foreseeing a decrease in the secondary benefits in 2016. The request was filed to the EFSD in September 2015.

Foreign policy coordination

Moscow de facto recognized its ally’s certain freedom of action in the regional and international arena that was the main result of the year in terms of the foreign policy cooperation. This recognition was particularly expressed as compliments to Minsk from Russian officials – Vladimir Putin and Sergei Lavrov – for the contribution to the peace talks on Ukraine and the facilitation of the trilateral contact group’s activities. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko has the reputation of a peacemaker since the negotiations of a contact group on the settlement of the crisis in eastern Ukraine in early September in Minsk with the participation of the OSCE and Russia when delegations of Kiev and the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics agreed to cease fire in the Donbas region.

The Kremlin seemingly decided that Minsk’s ‘neutral’ position can provide certain benefits. In conditions of half-isolation of Russia, elements of advocacy of its interests by Belarus brought new nuances in the foreign policy cooperation between the two states. Before, Moscow used to represent Belarus’ interests in the international arena when Minsk was not there for various reasons.

On March 10, Russia asked Belarus to represent its interests in the Joint Consultative Group on the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe.

During the visit to Georgia in April, Lukashenko offered his services as a consensus searching mediator between Russia and Georgia.

At the Riga Eastern Partnership summit in May, Belarus (together with Armenia and Azerbaijan) refused to sign the section of final declaration, which used the phrase “the annexation of the Crimea”, until there is a compromise version, in which only the European Union member states condemn the annexation.

In September and October, Belarus, which performed the function of the EEU Presidency, requested the observer status for the Union from the United Nations.

Belarus also joined the ‘Integration of Integrations’ campaign (‘Europe from Lisbon to Vladivostok’) launched by the Kremlin that involves the creation of prerequisites for a rapprochement between the European Union and the EEU. This topic was on the agenda of negotiations with European political and economic circles during the Belarusian-Austrian-Russian Business Forum on October 13 in Minsk. A lot was said about EU-EEU rapprochement at a meeting of the foreign ministers of Belarus and Russia on October 27.

‘Soft power’ pressure

While Russian and Belarusian officials were declaring full understanding on the whole range of issues and ‘similar positions’ on the resolution of the crisis in Ukraine (as Vladimir Putin said), some groups in Russia (including those affiliated with the government) were not that happy about the relatively independent position of Minsk.

In spring 2015, ‘offended patriots’ consolidated around the Russian news agency Regnum became highly active in the Russian media. Regnum and ideologically close Empire, Vzglyad and others intensified attacks against Lukashenko accusing him of indulging “the rampaging rabid nationalism” in Belarus saying that names of localities and some other names are written in the Belarusian language, there still are a few places where teaching is in the Belarusian language, the state media sometimes mention historical figures associated with the Belarusian (not Russian) history, and so forth.

This media noise was accompanied by a less noticeable, yet, perhaps more important (in the long term) activity of new expert groups formed mainly of persons having dubious professional reputation, like the authors of the document ‘Belarusian Nationalism against the Russian World. Final Report on the Activities of Extremist and Nationalist Organizations in Russia and the CIS’ presented in December 2015, as well as expert groups, which traditionally provide the Kremlin with expert reviews (e. g. the Higher School of Economics).

Activities of these groups mainly resulted from the opened channel of ‘soft power’ in 2014, when the Kremlin switched to attempts to pattern after the policies of western countries and foundations aimed at supporting non-governmental organizations, the mass media, think tanks etc. (including those in the neighboring countries). In April 2015, the Russian President signed a directive on state grants to NGOs in 2015.8 Old and new expert groups, including those pursuing the informational expansion of the ‘Russian World’, expectedly rushed into the opened channel right away.

Military cooperation

Economic problems and disagreements, and also the quite nervous reaction to the plan to place a Russian airbase in Belarus9 did not affect the military cooperation, which has developed normally.

A joint air defense exercise was held on September 10, and the next one was planned. In general, the nearest future of the airbase was decided as Belarus preferred it be: the deployment was postponed indefinitely, and the two governments agreed on procedures related to the urgent protection of Belarus’ airspace by Russian troops.

In January 2016, the Russian leadership approved a draft intergovernmental agreement with Belarus on the joint technical support for the regional force grouping.10 According to the draft, in times of peace, the Russian Defense Ministry accumulates and stores reserves of arms and materiel at its own stationary facilities, and only in case of an immediate aggressive threat moves them to Belarus. The use of the material and technical base of Belarus in wartime will be regulated by a separate agreement.

On June 16, Belarus signed a contract with Russian Helicopters on a supply of twelve Mi-8MTV-5 military transport helicopters to the Belarusian army “on the same conditions and with the same specifications as for the Russian armed forces.” In June, Belarusian Defense Minister Andrei Ravkov said that four divisions of Russian air defense missile systems S-300 would take up duty in Belarus by the end of 2015. The divisions arrived in early February 2016. The deliveries of S-400 are under discussion.

Conclusion

The economic cooperation will largely depend on the effects of the ongoing recession, which will be partly mitigated by the direct financial support in the form of loans and lifting of some restrictions on supplies of Belarusian commodities.

Direct contacts with the heads of Russian regions are likely to play a certain (but not determining) role in the restoration of exports to the Russian Federation.

In 2016, the political cooperation will most likely be maintained in a friendly atmosphere. In that case, Belarus will try to increase its role as Russia’s advocate in the relations with the outside world (in particular, Ukraine, Turkey and the European Union), and a lobbyist of EEU interests in the relations with some nations and international organizations (India, Vietnam and the United Nations).

A certain revitalization of the relations within the Union State is also possible. In 2016, the Union members will work on a joint military doctrine. This work is likely to take the whole year.