|

Presidential Election: Sociology of electoral stability

Sergey Nikolyuk

Summary

In the last year of the president’s five-year tenure, Belarusians had anxious expectations, which even the November surge in wages could not calm down. Anyhow, Lukashenko managed to accomplish his prime task by scoring another election Victory. However, the price of this Victory remains unclear either to himself or his political opponents. The official recognition of a split in society is just one of the consequences.

Tendencies:

- Electoral support for Lukashenko declined basically due to resource problems of the government aggravated by the global recession;

- Redundancy of opposition candidates did not affect their electoral ratings;

- The electoral structure of Belarusian society has not undergone essential changes over the years of independence;

- The ‘winner-takes-it-all’ election deepened the split in Belarusian society.

Final outcome

The outcome of the fourth presidential election (see Table 1 for voting patterns) did not surprise independent sociologists1 . With an 87% turnout, Lukashenko was in the lead by 59 percent to 32 percent received by the eight oppositional politicians. Only Viktor Tereshchenko and Dmitry Uss found themselves beyond the eight others but it did not change the picture considerably.

Table 1. Answers to the question “Who did you vote for at the last presidential election? (% of respondents)

|

1994 |

2001 |

2006 |

2010 |

А. Lukashenko |

35 |

48 |

58 |

51 |

Democrats |

26 |

21 |

24 |

28 |

Other contenders |

19 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

No answer/do not want to answer |

2 |

9 |

5 |

4 |

Against all |

4 |

7 |

3 |

5 |

Did not vote |

14 |

12 |

8 |

12 |

As usual, the data provided by the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies (IISEPS) differ from the official results. The Central Election Commission (CEC) reported a 90.66% voter turnout, 79.7% ballots cast for Lukashenko, 14.0% for his opponents, and 6.3% against all. The difference between the IISEPS and CEC’s figures gets bigger from election to election. With regard to the total number of eligible voters, it made up 15.2% in 2001, 18.9% in 2006, and 21.1% in 2010.

The official election returns traditionally coincide with pre-election opinion polls conducted by the Presidential Administration’s Information-Analytical Center (IAC) within the accuracy of 1%. According to the last polls arranged by salaried sociologists, Lukashenko was supposed to have 80.5%, his opponents were given 14.5%, and 5% were at a loss to answer. And so it happened, notwithstanding that IAC counted poll respondents and CEC counted voters.

The IISEPS however did not second the opposition politicians’ belief that a new electoral situation was observed in Belarus. With this belief in foundation, they constructed a whole Victory strategy with a crowd in the central square of the capital as a concluding chord. On the other hand, the figures published by SOCIUM International Center for Sociological and Marketing Research (33.3% for Lukashenko, 15.1% for Neklyaev, 10.6% for Sannikov, and 8.2% for Romanchuk) met the oppositional candidates’ expectations the most.

The sociological characteristics of Lukashenko’s electoral base did not change considerably in 2010. He enjoyed support of 24% of voters at the age of 18 to 19 and 73% of those at the age of 60 and over. Education: grade school graduates – 69%, university graduates – 46%. Social status: state sector employees – 53, non-state sector employees – 32%. Population cluster type: the capital – 40%, villages – 62%. Taking into account that the average female human life expectancy is considerably higher than that of men and women are less inclined to take risks and therefore prefer to work for state-run enterprises, Lukashenko’s constituent body still has “a woman’s face” with 59%against 41%.

Structural stability

Three more candidates – Alexandr Dubko, Vyacheslav Kebich, and Vasily Novikov – fought for a return to the “Soviet past” in 1994 alongside Lukashenko. All four harvested 54% (35% + 19%). It means that the structure of the Belarusian electorate has not changed or changed slightly since the first presidential election.

Opinion polls did not detect any new tendencies regarding the respondents’ intent to protest against the election results in case of improper ballot procedures (Table 2). It should be taken into account that the figures, which indicate respondents’ willingness to take any actions, are just declarations of intent. Some sort of a social trigger is needed to make them pass from words to deeds. The “color revolutions” – first of all the “orange” revolution in Kyiv – were such a trigger in 2006. In 2010, the trigger carried a “Made in Belarus” tag, and it was put there by the authorities, which wanted a “cheerful” election.

Table 2. Dynamics of answers to the question “What would you do believing that the presidential election was rigged?” (% of respondents)

|

Aug 2001 |

Feb 2006 |

Oct 2010 |

I will resign myself to this because there’s no getting away from it |

44 |

37 |

41 |

I will take part in mass protest rallies trying to change the outcome |

10 |

9 |

11 |

I will not trust the official results and they will disappoint me greatly, but I will not take part in mass protest rallies |

25 |

35 |

24 |

I am at a loss/do not want to answer |

21 |

19 |

24 |

The relative invariableness of the number of those ready to protest publicly is one more indicator of steadiness of the Belarusian electorate’s structure.

An explanation for this steadiness should be looked for in the “Belarusian economic model” announced during the seminar arranged for republican and local executives in March 2002. Specifically, it rests upon a strong and effective government, priority of state interests over interests of individuals, and privatization aimed at attraction of a “motivated investor”. Under these social and economic conditions, the country sees invariably high share of state property (nearly 80%) and invariably high number of citizens lacking skills for survival without parental care of the state.

The role of propaganda in regulation of people’s behavior should not be overestimated. It is the routine practices that make the people what they are in this respect. In November 1994, the number of centrally planned economy supporters in Belarus constituted 46% and free market economy advocates made up 51%. By September 2010, the number of the first reduced to 16%, while the latter were up to 67%. The basic changes fell within a short time period between 1994 and 1997. The economic preferences of the Belarusians practically did not change in the 2000s.

However, the state property prevalence itself does not explain much. In the Soviet Union, private ownership of the means of production was under a legal and ideological ban that could not prevent the “largest catastrophe of the XX century.” The Belarusian economic model is not a thorough reconstruction of Soviet patterns. In the opinion of its chief architect, “the distinctive feature of our model is a strong social policy of the state.” It is really hard to find another country amid the global recession, the leaders of which would spare no efforts to fulfill pre-crisis social commitments with manic persistence.

As a matter of fact, Lukashenko started his fourth election campaign on December 30, 2009 by giving wages a sacral status. “As to the wages, you know, we undertook a commitment: average wages must reach 500 U.S. dollars within a year. This figure is sacred! It was established at the All-Belarusian National Assembly five years ago. We must do it!” he said in a meeting with reporters of Belarusian national and regional media outlets.

Lukashenko’s lowest electoral rating ever was reported in March 2003 (Table 3). It was caused by slowed down growth in real value of cash incomes of the population, but then the advance in oil prices reversed the trend dangerous to the government. The households’ real incomes had been showing a double-digit growth for five years in a row, 2004 through 2008. For this reason, a 60% rating in the third presidential election year is not something incredible.

Table 3. Fluctuations in A. Lukashenko’selectoral rating (% of respondents)

Mar 2003 |

Apr 2006 |

Sep 2008 |

Dec 2008 |

Mar 2009 |

Jun 2009 |

Mar 2010 |

Jun 2010 |

Sep 2010 |

Oct 2010 |

Dec 2010 |

26 |

60 |

43 |

40 |

39 |

41 |

43 |

46 |

39 |

44 |

51 |

The income growth stopped in 2009 but it did not affect popularity of the only Belarusian politician in any way. The global recession came in handy to shift the blame onto. This shift would certainly be impossible without accompanying explanations provided by the governmental mass media. Lukashenko’s rating dropped just 4 points between the last pre-crisis poll conducted in August 2008 and that of March 2009 when the social indicators were down to the 2000s’ minimum.

The entire year 2010 passed under the banner of struggle for the “sacred figure”. In conditions of resource scarcity, the wage hike from the level of 381 dollars was achieved owing to the final spurt in November 2010 that called for a 31% increase in the first grade wage rate and a 55% increase in the minimum wage. Five years ago, 61% of the Belarusians believed in doubling of wages in the U.S. dollar equivalent. In December 2010, only 36% believed in 500-dollar wages. This paradox is probably one of displays of people’s anxiety on the threshold of the presidential election. The National Bank’s statistics seems to reflect this anxiety the best: in 2010, the net purchases of foreign currencies by the population exceeded 1.5 billion dollars. In the last analysis, this anxiety resulted in a 7% decrease in Lukashenko’s electoral rating as compared with “well-heeled” 2006.

The Belarusian version of a “strong social policy” should not be narrowed down to increase in wages and retirement benefits. Maintaining of the social stratification close to the European level is another component. “Everyone in the world says now that in our country incomes of the poor, roughly speaking, are lower than incomes of the rich 3 to 4 times, like in Sweden where this index is the best in the world,” Lukashenko said, “It is 25 to 30 times in Russia, which is catastrophic. It is a prerevolutionary situation.” The figures that Lukashenko referred to are the decile dispersion ratio, which presents the ratio of the average income of the richest 10 percent of the population divided by the average income of the bottom 10 percent. According to the official statistics, these figures are 5 to 6 in Belarus and 17 in Russia, but most Russian experts believe that the Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat) understates the decile dispersion ratio essentially.

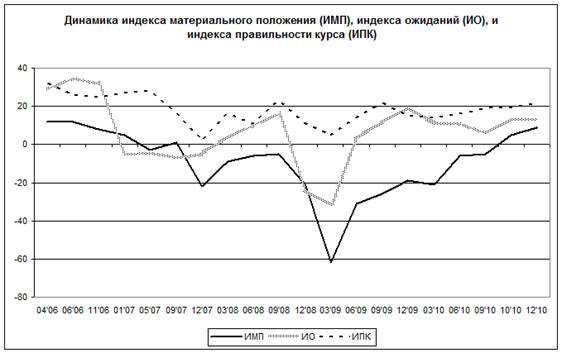

Successes and failures of the Belarusian government in fulfillment of the social obligations assumed at the III All-Belarusian National Assembly are vividly illustrated by the changes in social indexes, i.e. the difference between positive and negative answers to the three basic questions: “How has your personal financial status changed in the past three months?” (Financial Status Index, FSI), “In your opinion, how is the socioeconomic situation in Belarus going to change in the next few years?” (Expectations Index, EI), and “In your opinion, is the situation in our country changing in a right or wrong way?” (Policy Correctness Index, PCI).

In the year of the third presidential election, the values of all three indexes were the highest over the past five years (Fig. 1). The year 2007 began with a doubled price for Russian gas. The informational confrontation that followed resulted in a 37 point drop of the EI at once. We note that the EI is known for the greatest “fearfulness.” This index is usually the first to react to negative information. As to the FSI, it is determined “by the life itself.” Its crushing in December 2007 was a direct result of the doubled sunflower oil prices. The global financial crisis had been the major factor affecting social mood since late 2008. Its perception peaked in March 2009.

Fig. 1. Changes in the Financial Status Index, FSI (black solid line);

Expectations Index, EI (grey line) and Policy Correctness Index, PCI (dotted line)

However, the crisis was not as terrifying as it looked at first. In 2010, the government engaged in ramping up wages and pensions. By the time of voting, the social indexes were up to an appreciable level, although they did not reach the values of 2006. Lukashenko’s electoral result was lower accordingly.

Recognition of a split

Official recognition of a split in Belarusian society was an important result of the fourth presidential election. During the press conference held December 20, 2010, the day after the violent disruption of the rally in the Independence Square, Lukashenko said, “Let’s be honest: 20% either voted against or voted for alternative candidates. We must admit that there is plenty to think about.”

We remind that the comment on the outcome of the 2006 election was totally different. Lukashenko put the Central Election Commission head in an awkward position saying more than once that the election was deliberately engineered. In an interview to First Deputy Director General of ITAR-TASS News Agency Mikhail Gusman in August 2008, he said literally, “For your information, I polled 93% in the past election. And I admitted afterwards, when they started to pressurize me, that we fixed the election. And I put it straight, “Yes, we did.” I ordered to make it not 93% but around 80% or something, I do not remember, because 90% is beyond psychological comfort. And that was the truth.” In the New-Year greeting speech, Lukashenko addressed the “majority” and “minority” for the first time instead of the “solid Belarusian family.”

The split in Belarusian society is no secret for those who stays updated on independent opinion polls. It comes out with every answer to a politics-related question. Each part of Belarusian society takes an independent stand on the financial status changes, Belarus’ development prospects, and states opinion on development trends. If to calculate the social indexes separately in relation to those who trusts Lukashenko and those who do not (Table 4), it would look like the first live in Switzerland, and the rest live in Somalia.

Table 4. Values of social indexes depending on the attitude to Lukashenko (Financial Status Index (FSI), Expectations Index (EI), Policy Correctness Index (PCI))

|

FSI |

EI |

PCI |

All respondents |

9 |

13 |

22 |

Trust Lukashenko (55%) |

30 |

45 |

72 |

Do not trust Lukashenko (34%) |

–28 |

–26 |

–52 |

The Belarusian variant of a split does not suggest a dialogue between the “official” and “independent” communities. The official recognition of the “minority” does not mean that dissentients will be given floor to voice their priorities. On December 20, Lukashenko promised “to think”, but the result of his intellectual efforts have not been given public utterance yet. Meanwhile, any split is a frozen revolution, and not necessarily a “color” one.

1 Data provided by the IISEPS here and below. See www.iiseps.org

|